1776: The Beginnings of American Exceptionalism Abroad

Between Republic and Empire: How Constitutional Ratification Rejected Isolationism

Share On:

On September 28, 1787, the Confederation Congress transmitted a new plan of government to the states for consideration. The proposed U.S. Constitution ignited a firestorm of pamphlets written by Federalists, who urged ratifying the document, and so-called Anti-Federalists, who opposed ratification. Launching an early salvo in the yearslong fight was the pseudonymous “Brutus.” The pen name said it all—like the patriot who assassinated Julius Caesar, this Anti-Federalist too stood against empire and for the preservation of the republic. In his first letter, Brutus argued against consolidating the states under a national government. As he saw it, the Federalists and Anti-Federalists shared the goal of perpetuating a free government that secured liberty for all, leaving only the question of means. Which form of government was more likely to attain the goal: a confederation of thirteen sovereign republics, as prevailed under the operative Articles of Confederation, or the newly proposed national government?

For Brutus, the answer was clear. Theory, history, and reason had already decided the question. Following Montesquieu, who taught that republics were naturally small, Brutus insisted theory proves that the public good is more intelligible in homogeneous communities. In large and diverse polities, by contrast, it is “sacrificed to a thousand” contending visions of the good. History too was on his side. Greek and Roman republics were small. But once they expanded, they degenerated into tyrannies. Finally, reason had rendered the same verdict. No democracy, not even the representative sort outlined in the Constitution, could exist over a large territory. Representatives must “know” and “declare the minds of the people” for whom and on whom they legislate. Brutus doubted a representative sitting in the capital of Philadelphia, sent from constituents in New Hampshire, could apprehend the interests of frontiersmen in Georgia even as he drafted and debated legislation that would determine the future of the frontier.[1]

A month later, James Madison, writing as “Publius,” famously flipped Brutus’s admonition on its head in Federalist No. 10. Republics do not collapse under the weight of competing visions of the public good, he wrote; they die when one faction, with one particular vision, dominates others. The undoing of the ancient republics was not their largeness, but their smallness, which made them vulnerable to factional capture. And democracy worked best when diverse interests clashed in legislatures. The solution, then, to preserving American exceptionalism—the experiment in self-government then being tested across the eastern seaboard—was consolidating states, extending the republic across the continent, and thereby diluting factional influence.[2]

The exchange between Brutus and Madison anticipated debates that would animate the ratification conventions that unfolded over the next few years in each of the thirteen states. At the heart of the dispute between the Anti-Federalists and the Federalists was a disagreement, as Madison put it months later at his state’s convention, over the “means of preserving and protecting the principles of republicanism.”[3]

Both the Constitution’s proponents and its opponents agreed that their fledgling federation was exceptional. This Union of republics had thrown off the yoke of imperial domination and embarked on an experiment in self-government on an unprecedented, continental scale. Both camps agreed that the Union, whatever form it took, should expand.

The camps disagreed, however, over the means of safeguarding the uniquely republican character of the Union and the territory it was destined to settle. Federalists contended that, but for adopting the Constitution, the Union would lack the tools and cohesion for survival. Preserving the republic required consolidating states under a national banner, of course, but also enlarging that banner’s orbit and, crucially, shaping its environment. An infant republic could not long endure in a world inhospitable to republicanism. Had America’s weakness and isolation, Federalists asked, not caused her strategic encirclement, left her sailors vulnerable to capture, and forfeited her right to navigate the Mississippi? Self-rule at home could be guaranteed only by extending what Thomas Jefferson called, as early as 1780, “the empire of liberty.”[4]

But this “great consolidated empire” that the Constitution promised was “incompatible with the genius of republicanism,” charged the Anti-Federalists.[5] Republican government, it was well known, could not survive over an expanse so large as the territory awarded the United States in the 1783 Paris Treaty. And it certainly could not long endure by cooperating with monarchies or competing with empires. Engagement with Old World regimes would lead to imitation, betraying the spirit of the Revolution that made America exceptional. Had the alliance between these thirteen sovereign republics, the Anti-Federalists asked, not proved its mettle by defeating the British Empire? Had modern confederations not prospered by avoiding great-power rivalries? Had the ancient republics not ruined themselves by their pursuit of empire? Republican home rule could only be guaranteed by resisting delusions of grandeur abroad.

When, between 1787 and 1790, the Constitution was debated, devised, and redebated in the states, both the Federalist and Anti-Federalist visions for preserving American exceptionalism were untried. Both camps’ theories were plausible. Because they agreed America was indeed an exception, nobody could reliably ascertain from history or experience what its perpetuation would require.

This essay reconstructs the camps’ contrasting visions, illustrates how they manifested in the history of the early republic, and suggests how each resonates in U.S. foreign policy today. Whatever the merits of the Anti-Federalist case at the Founding, and though their concerns echo throughout American history, bearing fidelity to our Constitution demands we recognize ratification for what it was: a repudiation of the Anti-Federalist theory of preserving American exceptionalism through American isolation. Through ratification, the Founding generation embraced the Federalists’ arguments that happiness at home depended on strength abroad, that external threats outweighed internal ones, and that the preservation of American exceptionalism depended on shaping the country’s international environment.

Approaching “the Last Stage of National Humiliation” on the Eve of Ratification

That decision to side with the Federalists did not occur in a vacuum, of course. It had much to do with the Union’s grim geopolitical position at the time. Though Anti-Federalists complained that their rivals were inflating external threats to scare them into ratifying the Constitution, they could not credibly dismiss the strategic vulnerabilities their states then faced.

The Treaty of Paris (1783) had officially secured American independence, but it did not deliver peace and security—far from it. Independence brought a host of new challenges—most urgently, how to survive as a lone, loosely knit republic encircled by predatory empires. The United States was menaced on all sides: by British garrisons in the northwest forts, Spanish settlements to the south and west, Indian confederacies along the frontier, and Barbary pirates on the high seas. The Confederation Congress proved impotent in the face of the threats. It could not enforce the terms of the peace treaty, assert American rights to navigate the Mississippi, or even prevent its seafaring merchants from becoming hostages. As Alexander Hamilton put it, the Union had “reached almost the last stage of national humiliation.” “We have neither troops, nor treasury, nor government” to change the situation.[6]

Winning the Revolutionary War had not even expelled British troops. In violation of the treaty, British regulars refused to evacuate frontier posts in present-day Michigan, Ohio, and New York. The affront was particularly galling given the origins of the late war. After colonists had fought for the British Empire in the Seven Years’ War, the Crown issued the Proclamation of 1763, which, in an effort to stabilize relations with Native Americans, purported to prevent colonists’ westward expansion. Long before the Stamp Act, Intolerable Acts, and the rest, the Proclamation had laid the groundwork for war.[7] The rebels’ victory now appeared hollow in light of continuing British efforts to hem in American expansion. Britain cited American states’ own failures to honor treaty promises—including collecting prewar debts owed to British creditors and restoring confiscated Loyalist property—to justify its continued presence.[8] Worse, Congress’s inability to impel states’ compliance risked furnishing London with a casus belli to resume hostilities at a time of its choosing. Adding insult to injury, British trade policies barred U.S. ships from the lucrative West Indies and flooded American markets with British goods, deepening an economic depression.

Things looked bleak to the south, too. While “Britain excludes us from the Saint Lawrence” in the north, “Spain thinks it convenient to shut the Mississippi” to American commerce in the south, lamented John Jay.[9] Closure of the latter in 1784 threatened to sever the lifeline of frontier communities in Kentucky and Tennessee. The “state” of Franklin (in present-day Tennessee) flirted with seceding so its inhabitants could negotiate directly with Spain. Spanish forces arrayed along the Gulf Coast, and the Creeks they armed, resisted U.S. encroachment south.[10] Hemmed in by imperial rivals who manipulated borderland conflicts to their advantage, U.S. settlements and territorial claims remained in a precarious state. A South Carolinian legislator gloomily observed that Americans only “hold the property that we now enjoy at the courtesy of other powers.”[11]

On the high seas, Americans fared little better. Stripped of the Royal Navy’s protection and having disbanded the Continental Navy after the war, U.S. merchant ships were defenseless prey for the Barbary principalities of North Africa. Algerine corsairs captured American vessels and enslaved their crews, knowing the American government had neither warships to retaliate nor funds to pay ransoms. By 1786, dozens of American sailors languished in Algiers. With only some hysteria, a Federalist from North Carolina asked, “[w]hat is there to prevent an Algerine Pirate from landing on your coast, and carrying your citizens into slavery?” The country had recently sold its last frigate, leaving it without “a single sloop of war.”[12] To revitalize trade in the Mediterranean and elsewhere, the Union needed a navy, treaties, or at least cash for ransom. The Confederation Congress could provide none of the above.

“Foreign nations are unwilling to form any treaties,” explained Madison, because they knew Congress could not keep its promises, pay its debts, or bind the states to a uniform commercial policy. The few treaties Congress had managed to conclude were routinely flouted by powers who rightly surmised that the “notoriously feeble” Congress could not enforce compliance.[13]

Before the war, colonists had grown disgruntled over mercantilist policies that made them “dependent . . . on Great-Britain.” After winning the war, Connecticut’s Oliver Ellsworth complained, Americans now relied on the good graces of “every petty state in the world and every custom house officer in foreign ports.”[14] Restricted to a few foreign ports, American merchants “must sell low, or not at all.”[15] “Was there an English, or a French, or a Spanish island or port in the West Indies,” Jay asked in exasperation in late 1787, “to which an American vessel can carry a cargo of flour to sale? Not one,” he answered.[16] Jay’s own attempt to negotiate a commercial treaty with Spain collapsed the year before, a casualty of U.S. sectional divisions and Spanish intransigence.[17]

The economic consequences of American impotence were on full display at the nation’s ports. After dissolving the navy, a Pennsylvania Federalist described the “melancholy countenances of our mechanics, who now wander up and down the streets of our cities without employment,” condemned to watch “our ships rotting in our harbors.”[18] Meanwhile, New York’s docks were crowded with foreign vessels—“sixty ships, of which fifty-five are British,” one newspaper reported.[19]

The American experiment in independence was imperiled by external danger and internal infirmity. Congress could not tax and thus could not pay its debts or fund defense; it could not regulate commerce and thus could not counter foreign discrimination; it could not enforce treaties and thus could not shape the geopolitical environment to its favor.

It was against this foreboding backdrop that delegates convened in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 to draft a new constitution. There, they confronted, debated, and answered fundamental questions with direct foreign-policy consequences: What was the purpose of the Union? Which dangers posed the greatest threat to that purpose? And what lessons could history teach about the fate of republics? Each question would reemerge at the states’ ratification conventions. Through ratification, Americans embraced the Federalists’ answers.

Domestic Tranquility vs. Common Defense? Debating the Ends of American Government

Among the chief purposes of the proposed Constitution, as the document’s preamble made clear, was to “insure domestic Tranquility, [and] provide for the common defence.” Anti-Federalists figured this first sentence of the document was as good a place as any to begin their attack. The Anti-Federalists argued that these ends worked at cross purposes: a robust, federal capacity to provide defense necessarily imperiled domestic tranquility. The Federalists, on the other hand, saw the two aims as indivisible: there could be no domestic tranquility without a credible common defense.

This dividing line animated the ratification fight but first surfaced at the Constitutional Convention itself. When, early in the months-long debate, South Carolina’s Charles Pinckney asserted that “the great end of Republican Establishments” is a government “capable of making [citizens] happy at home,” this Federalist unwittingly foreshadowed an argument the Anti-Federalists would stress. “We mistake the object of our government if we hope or wish that it is to make us respectable abroad. Conquest or superiority among other powers is not or ought not ever to be the object of republican systems.” “[A]ll we can expect” of a republican government, Pinckney concluded, is that it “preserve our domestic happiness & security.”[20]

Nonsense, howled New York’s Alexander Hamilton. Pinckney had drawn a false, “ideal distinction” between domestic contentment and national power. “No government could give us tranquility and happiness at home, which did not possess sufficient stability and strength to make us respectable abroad.”[21] How could a man find happiness if his government was too ineffectual to open ports to his crops or too weak to defend his land from invasion? National strength was a precondition of Americans’ security and prosperity.

Pinckney and Hamilton’s exchange prefigured the ratification debates, where Anti-Federalists maintained that the Union’s raison d’être had already been decided by the Declaration of Independence—securing “Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” The proposed Constitution, in their estimation, forgot these ends. Worse, by vesting in a national government the unlimited power to tax and raise standing armies for national defense, Federalists had betrayed the revolutionary spirit that had made America exceptional. [22]

Brutus flatly asserted, “the protection and defense of a country against external enemies . . . is not the most important, much less the only, object of [government’s] care.” Rather, “the happiness of a people depends infinitely more” on good governance of local matters. European monarchies, oriented as they were to martial success, “mistake the end of government—it was designed to save men[’]s lives, not destroy them.” Let them “share among them the glory of depopulating countries, and butchering thousands of their innocent citizens,” and let Americans pursue “happiness among ourselves.” A Constitution that made national strength possible, Brutus feared, would make the nation’s imitation of the Old World inevitable. By rejecting that Constitution, America would not only avoid costly, pointless wars but perhaps even “furnish the world with an example of a great people” worthy of its own imitation.[23]

None, however, made this case more frequently or forcefully than Patrick Henry, the two-time governor of Virginia and leader of the Anti-Federalist charge at his state’s convention. The erstwhile rebel who once stirred revolutionary fervor by crying “give me liberty, or give me death!” had, to his astonishment, overnight become “an old fashioned fellow” for his “invincible attachment” to the Declaration’s principles. He saw in the proposed Constitution “a revolution as radical as that which separated us from Great Britain,” only this revolution would reverse the blessings of the last. Clearly, Henry surmised, the Constitution’s drafters had contemplated “how your trade may be increased” and “how you are to become a great and powerful people.” Less clear was whether they paid much mind to “how your liberties are to be secured,” which “ought to be the direct end of your Government.” Mocking the Federalists, Henry asked his fellow delegates: “But, sir, we are not feared by foreigners: we do not make nations tremble[.] Would this, Sir, constitute happiness or secure liberty?”[24]

The Anti-Federalists for whom Henry spoke were convinced that consolidation of the states portended empire, and from empire would follow the fall of the republic. If the proposed Constitution “squint[ed] toward monarchy” with intrigue, as Henry suggested it did, he was sure it stared at empire with envy. Henry demanded to know:

Shall we imitate the example of those nations who have gone from a simple to a splendid Government? Are those nations more worthy of imitation? What can make an adequate satisfaction to them for the loss they suffered in attaining such a Government for the loss of their liberty? . . . Some way or other we must be a great and mighty empire; we must have an army, and a navy, and a number of things: When the American spirit was in its youth, the language of America was different: Liberty, Sir, was its primary object. . . . But now, Sir, the American spirit, assisted by the ropes and chains of consolidation, is about to convert this country to a powerful and mighty empire.[25]

This “great consolidated empire of America,” Henry concluded, was plainly “incompatible with the genius of republicanism.”[25]

The Federalists’ reply mirrored the exchange at the Constitutional Convention. Just as Hamilton had criticized Pinckney for failing to see how Americans’ happiness depended on the nation’s standing abroad, Madison now pressed Henry to explain how the United States could be “secure and happy at home” without being “respectable abroad?”[26] Governor Edmund Randolph scolded Henry’s tunnel vision along similar lines. “The magnificence of a royal court is not our object,” he explained. We want only a country that can “give us security.” And a country “contemptible in the eyes of foreign nations” could not provide it, for “contempt . . . is too often followed by subjugation.” Whereas Henry feared subjugation under the heels of a peacetime army, Randolph saw subjugation as the price of forgoing that army. Look at “our situation,” he demanded: “Does not it invite real hostility?”[27] For the Federalists, domestic tranquility and common defense were not competing but instead indivisible ends.

Specters of the Republic’s Ruin: External Threats vs. Internal Usurpations

Closely related to this debate over the ends of the Union was a second key disagreement: what was the greatest threat to the young republic’s survival? The Federalists and the Anti-Federalists located the republic’s ruin in different places. The Federalists looked outward and saw the specters of foreign invasion, subjugation, or humiliation. The Constitution was a hedge against each. For the inward-looking Anti-Federalists, fatal threats lurked within the Constitution itself—an overweening centralized government that would extinguish liberty under the pretext of defense and unity.

Both sides accused each other of fearmongering to bypass a candid evaluation of the Constitution’s merits. The Anti-Federalists have insisted “that this Constitution ought to be rejected, because it endangered the public liberty,” Madison noted. But they have made only “general assertions of dangers.” “Let the dangers which this system is supposed to be replete with, be clearly pointed out.”[28] On the other hand, Henry charged, the Federalists have alluded to “great and awful dangers” that only the Constitution can keep at bay, but “it is not sufficient to feign mere imaginary dangers; there must be a dreadful reality. The great question between us is, Does that reality exist?”[29]

For Henry the answer was clearly no—only days before he had confidently informed the convention that “[h]appily for us, there is no real danger from Europe” or elsewhere.[30] He even cited private correspondence from Thomas Jefferson, then U.S. minister to France, to bolster his assessment that neither France, Britain, Spain, nor Holland harbored designs against the United States.[31] Ask the “poor man” if he fears for his safety and he will tell you he “enjoys the fruits of his labour, under his own fig-tree, with his family and children around him, in peace and security.”[32]

Anti-Federalists across the Union used similar talking points. “A Plebian” (likely Maryland’s Luther Martin or New York’s Melancton Smith) observed that Federalists painted a “high-wrought picture . . . that we were in a condition the most deplorable of any people upon earth. But “[d]oes not every man sit under his own vine and fig-tree, having none to make him afraid?” Knowing the “apprehension of danger is one of the most powerful incentives to human action,” the Federalists had exploited it. But the “prudent man,” A Plebian hoped, “will not be terrified by imaginary dangers.”[33] A “Federal Farmer” put the Anti-Federalist assessment most succinctly when he wrote, “[w]e are in a state of perfect peace, and in no danger of invasions.”[34]

The real threat, the Anti-Federalists were convinced, derived from the Constitution. A government strong enough to command respect abroad was certainly strong enough to subjugate the people at home. Even if the Federalists were right about the danger of foreign invasion, Anti-Federalists thought accepting this powerful government was effectively “committing suicide for fear of death.”[35] In the face of a national government vested with “unlimited and unbounded” powers to tax, raise armies, and commandeer state militias—powers that no Federalist denied the Constitution provided—“[w]hat resistance could be made?” Henry asked.[36]

The Federalists had both specific answers, grounded in the Constitution’s text, and a more general answer that disputed Henry’s premises. To Henry’s specific fear of citizen subjugation, Madison stressed that under the Constitution, Congress could only “call forth” the militia to repel invasions, quell insurrections, or execute the Union’s laws (a broad condition precedent Madison strategically downplayed).[37] (In a sobering Federalist Paper, Madison wondered whether a national military, probably no more than 30,000-strong, could even do this should state militias—whose combined ranks numbered a half-million—resist Congress’s call.)[38] Without this power to enlist militiamen into national service, the country could be “conquered by foreign enemies” or have its freedom “destroyed by domestic faction.” The result of either event, Madison concluded, would be precisely the “domestic tyranny” Anti-Federalists most feared.[39]

The Federalists’ more general response was that constitutional provisions concerning the militias and providing for a standing army, far from threatening Americans’ liberty, were that liberty’s guarantors. If freedom flourished under peace, as the Anti-Federalists insisted, then a military was not an affront to but “an additional security to our liberty.”[40] In fact, it was the absence of military power that courted war. Because “[w]eakness will invite insults,” Madison warned, “[t]he best way to avoid danger is to be in a capacity to withstand it.”[41] He asked Anti-Federalists:

suppose a foreign nation [were] to declare war against the United States, must not the general Legislature have the power of defending the United States? Ought it to be known to foreign nations, that the General Government of the United States of America has no power to raise or support an army, even in the utmost danger, when attacked by external enemies? Would not their knowledge of such a circumstance stimulate them to fall upon us? If, Sir, Congress be not invested with this power, any powerful nation, prompted by ambition or avarice, will be invited, by our weakness, to attack us.[42]

When, in his 1793 annual message to Congress, George Washington observed that “[i]f we desire to secure peace . . . it must be known that we are at all times ready for war,” he was merely recapitulating the theory of deterrence by denial long espoused by Federalists.[43] In his May 1786 report to Congress, for instance, future Federalist contributor John Jay, observing Britain’s occupation of American territory, advised that “the United States should, if it were only to preserve Peace, be prepared for war.”[44] Likewise, in an early and widely circulated defense of the proposed Constitution, Pennsylvania’s James Wilson addressed complaints that the document “tolerates a standing army in the time of peace.” Even in times “of the most profound tranquility,” Wilson explained, the nation must “maintain the appearance of strength” to ward off opportunistic aggressors. A modest peacetime army was cheaper and less disruptive to liberty than raising one in a crisis invited by weakness.[45] The Constitution’s backers from Maine to Georgia insisted that readiness for war was “indispensably requisite for peace, dignity, and happiness.”[46] Proto-Reaganites, they advocated peace through strength.

The Anti-Federalists remained unconvinced. They saw America’s oceans as moats and its coastlines as buffers from European conflict, enabling the enjoyment of a splendid, republican isolation. More than a century later, French ambassador Jean-Jules Jusserand captured how Anti-Federalists saw their country’s geographic blessings: “on the north, she has a weak neighbor; on the south, another weak neighbor; on the east fish, and the west fish.”[47] As Brutus put it before, “[w]e have no powerful nation in our neighbourhood.” While some European empires “have provinces bordering upon us,” they pose little threat. To attack us “they will have to transport their armies across the Atlantic, at immense expense.”[48] Even if European powers wished to attack America, “they cannot starve us out; they cannot bring their ships on the land,” claimed General Samuel Thompson of Massachusetts (apparently forgetting that his recent foe had done just this).[49] “We have been told of phantoms” to scare us into funding a navy, charged the Virginian William Grayson, pretending to tremble at the prospect of Barbary pirates “fill[ing] the Chesapeake with mighty fleets.”[50] As far as the Anti-Federalists were concerned, oceans rendered the risk of surprise negligible and the margin for strategic error wide.

Federalists, by contrast, saw America’s oceans as highways and its coastlines as beachheads for European armies. “Whoever considers the peculiar situation of this country[,] the multiplicity of its excellent inlets and harbours, and the uncommon facility of attacking it,” Madison stated, “cannot hesitate a moment in granting” Congress the power to maintain a navy and keep an army.[51] No state alone could adequately provide for its defense against a European army and the “phantom of a General Government” that we call the Confederation would be no help, he wrote. The coastline, and particularly the island of New York City, could rightly be “regarded as a hostage for ignominious compliances with the dictates of a foreign enemy, or even with the rapacious demands of pirates and barbarians.” When war again broke out in Europe, it would surely “be let loose on the ocean.” And it would “be truly miraculous” if America could then somehow “escape [war’s] insults and depredations” without a formidable military deterrent.[52] While the Federalists saw external threats just over the horizon, the Anti-Federalists thought it would be truly miraculous if America could somehow avoid tyranny with a robust military.

American Exceptionalism & the Limits of History

History was a double-edged sword in the ratification debates. Both sides could, and did, plumb the historical record to pad their briefs. Yet neither side could find the perfect analogy because, all agreed, America was exceptional. Her experiment with self-government was playing out on an unprecedentedly large canvas. Her size—indeed, the size of North Carolina alone—already defied Montesquieu’s recommended extent for a republic. Were we to let a dead French theorist decide our fate, Hamilton scoffed, “we shall be driven to the alternative either of taking refuge at once in the arms of monarchy, or of splitting ourselves into an infinity of little, jealous, clashing, tumultuous commonwealths.”[53] Moreover, because, as Madison put it, the proposed government had no “express example in the experience of the world,” history may be a poor guide.[54]

Still, both sides drew from history in efforts to corroborate their predictions. While Anti-Federalists leaned on the lessons of antiquity, which associated expansion with decline, the Federalists pointed at the contemporary map, where confederacies that refused to consolidate and expand to defensible borders were systematically picked off, partitioned, and recolonized.

According to Anti-Federalists, the verdict of history was clear. “[T]hose nations who have gone in search of grandeur, power, and splendor have . . . been the victims of their own folly. While they acquired those visionary blessings, they lost their freedom,” Henry recounted. The relevant examples “are to be found in ancient Greece and ancient Rome,” where we learn “of the people losing their liberty by their own carelessness and the ambition of a few.”[55] “It is ascertained by history,” confidently declared Henry’s ally George Mason, “that popular Governments can only exist in small territories. Is there a single example, on the face of the earth, to support a contrary opinion?”[56]

Perhaps not, but Federalists were confident that contemporary history also showed that small republics faced their own challenges. They pointed to the fledgling Swiss Confederation. American territory was more vulnerable than the Swiss cantons because the latter had the protective Alps and the sufferance of ascending European powers whereas the United States had coveted fertile, flat lands and no great-power patron. Federalists also noted that the Dutch Republic had been constantly at war despite its commercial wealth (Britain had even recently defeated it for aiding the American Revolution). The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth provided the starkest warning: weak central authority there had led to its partition at the hands of her imperial neighbors.[57] Only through “adoption of the new Constitution,” they argued, could America’s own “dismemberment” be avoided.[58]

The Federalists’ crucial move, however, was de-emphasizing the relevance of history. Because all agreed that the Revolution was fought to chart a new path, no historical analogy would have great persuasive force. The past offered cautionary tales, to be sure, but few clear guides. “If we go over the whole history of ancient and modern republics,” contended Madison, and “consider the peculiar situation of the United States, and what are the sources of that diversity of sentiments that pervades its inhabitants,” we would see that the best “means of preserving and protecting the principles of republicanism will be found” in this very constitutional scheme before us.[59] Thanks to our understanding of this “new science of politics,” wrote Hamilton, the United States would thrive where other republics had failed. In addition to the separation of powers, checks and balances, and popular representation, the most “novel” modern discovery was that, pace Montesquieu, “the ENLARGEMENT of the ORBIT” of a republic not only enhances “security” against “external force” but also promotes the “internal tranquility of States.”[60]

Put differently, the promise of liberty lay not in compactness and homogeneity but in scale and variety. It was the smallness of “the petty Republics of Greece and Italy,” not unlike the smallness of Rhode Island and Delaware, that made them susceptible to constant tumult, wrote Hamilton.[61] Expanding the distance and diversity of the country, Madison had posited some time before the Constitutional Convention, would frustrate factional collusion. Therefore, “the enlargement of the sphere” was pivotal to protecting the “private rights” Anti-Federalists so jealously guarded.[62]

The Federalists believed that, through expansion and consolidation, they had discovered a formula for empowering government without destroying liberty. Anti-Federalists, of course, remained skeptical that such alchemy was possible. More likely, they figured, the Federalist plan would merely establish a European-style empire in the New World.

Federalists, for their part, did not flinch from describing America, or at least her potential, as an empire. They embraced it. At the Constitutional Convention, demands for provisions “supporting the dignity and splendor of the American empire” were not uncommon.[63] But this would be no ordinary empire. The American empire would be motivated by security over glory and animated by freedom instead of subjugation.

Hamilton’s conception of the American empire saw hegemony of the Western Hemisphere as a necessary condition for preserving American exceptionalism. “[O]ur situation invites us and our interests prompt us to aim at an ascendant in the system of American [i.e., Western Hemispheric] affairs.” Even though the world naturally divides into European, African, Asian, and American parts, “Europe, by her arms and by her negotiations, by force and by fraud, has . . . extended her dominion over them all.” She “consider[s] the rest of mankind created for her benefit.” The task of the United States, which Union alone “will enable us to do,” is “to vindicate the honor of the human race, and to teach that assuming brother [Europe] moderation.” Hamilton continued:

Let Americans disdain to be the instruments of European greatness! Let the thirteen States, bound together in a strict and indissoluble Union, concur in erecting one great American system, superior to the control of all transatlantic force or influence, and able to dictate the terms of the connection between the old and the new world![64]

Long before America had the material capability to enforce it, Hamilton wrote the blueprint for the Monroe Doctrine and foreshadowed the early-twentieth-century policy of hemispheric defense. Moreover, he made clear that unlike empires of old, the purpose of America’s imperial project would be to honor, not subjugate, the human race.

After Ratification: Vindications and Reflections of the Federalist Vision

After hearing both sides, Americans across the country—in the most democratic procedure yet undertaken—adopted the Constitution.[65] In so doing, they advisedly decided how the republic would be governed and preserved. Most obviously, they substituted a national government for a confederation of sovereign states. They replaced a unicameral Congress with a bicameral legislature, chief executive, and federal judiciary. And, crucially, they repudiated the Anti-Federalists’ theory of preserving American exceptionalism through isolation and embraced the Federalists’ theory of preservation through engagement.

Ratification decided three core debates with foreign-policy implications. First, rather than treat domestic tranquility and common defense as competing ends, Americans endorsed the Federalist view: but for a credible defense, there could be no peace and prosperity to protect. Being “happy at home” depended on being “respectable abroad.”[66] Second, while robust military capabilities had historically threatened citizens’ liberties, the graver threat facing the American republic was subjugation from without. The power to repel invasions and insurrections was the best assurance against the “domestic tyranny” Anti-Federalists so feared.[67] Third, key to preserving the American republic was the enlargement and consolidation of its orbit. While the Anti-Federalists read antiquity as a warning against expansion and engagement, Americans put their faith in what the Federalists called the “new science of politics,” which posited that stability and perpetuity depended on scale and diversity.[68]

Ratification made the Federalists’ foreign-policy theory a part of our supreme law. It did not guarantee that their theory would be always and faithfully observed, however. Even committed Federalists sometimes seemingly forgot what ratification had decided. When they forgot, history nevertheless tended to vindicate the Federalist theory. Early episodes of post-ratification history, such as the American “Quasi-War” with France, illustrate the point. In other respects, like the expansion and consolidation of the Union, American statecraft has tended to reflect the Federalist theory.

The Franco-American Quasi-War Vindicates the Federalist Vision

In his first State of the Union address, Washington recited the Federalist creed of peace through strength. Domestic tranquility—the “concord, peace, and plenty with which we are blessed”—could be secured, said Washington, only by providing for the common defense, including a standing army and a manufacturing base to equip it. He reminded Congress that “to be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.”[69]

But Congress failed to heed his admonition. Thus, shortly after Washington’s second term began, Americans were once again the collateral victims of great-power sparring. Having disbanded the navy—the last ship of the Continental Navy was decommissioned in 1785—the nation relied on diplomacy to secure its commerce and oceans to insulate it from European conflicts.[70] Neither worked.

After Britain declared war on France in early 1793, Washington’s Neutrality Proclamation sought to avoid entanglement and assert its right to free trade.[71] Both British and French sailors nevertheless continued hijacking U.S. merchant ships and impressing crews. Proclaiming neutrality, Americans discovered, was not so different than declaring independence: pronouncements are rarely self-enforcing in international politics and diplomatic outcomes often depend on coercive leverage.

With a proclamation to enforce but little leverage, Washington dispatched John Jay to Britain in 1794 to resolve the countries’ commercial and territorial disputes. To the French (and a nascent party of Jefferson’s backers, the Democratic-Republicans), the resulting “Jay Treaty” looked like an Anglo-American alliance and a de facto repudiation of the 1778 treaties made with the now-deposed French Crown. The French responded by intensifying attacks. Equipped with lettres de marque, privateers acting under the color of French law seized more than 316 U.S. commercial ships between October 1796 and June 1797 alone.[72] So defenseless were American coasts that French corsairs regularly captured U.S. merchants just off the eastern seaboard and even docked in American ports.[73]

Hoping to avoid all-out war with France, President John Adams sent a bipartisan mission to the French Directory in July 1797 to negotiate a “Jay Treaty” for France.[74] Once arrived, the French added insult to injury. For months, the French foreign minister denied the American envoys an audience. Eventually, they were approached by the minister’s intermediaries—later dubbed “X,” “Y,” and “Z” in Adams’s report to Congress—who demanded bribes, loans to pay U.S. claims against French privateers, and public apologies, all before talks could begin.[75] When news of the so-called “XYZ Affair” reached Americans, sentiment coalesced around the rallying cry of a Federalist congressman from South Carolina: “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.”[76]

The Adams administration exploited the outrage to invest in a naval buildup and coastal fortifications long deemed unnecessary and provocative by the Democratic-Republicans. The government finished top-of-the-line frigates that might otherwise have gone abandoned. It directed the newly established Department of the Navy to arm merchant vessels and escort them through international waters. And it took the fight to the French. American privateers, carrying their own letters of marque furnished by Congress, interdicted French trade and reclaimed U.S. vessels in the West Indies. Between 1796 and 1800, the U.S. Navy’s fleet grew tenfold.[77]

By the end, the French reluctantly agreed in the Treaty of Mortefontaine to extinguish existing treaties between France and the United States and to stop interfering with the latter’s rights to neutrality and free trade. In short, only once the United States had proven its capability did France concede what Washington’s Proclamation had declared years ago.

The origins and resolution of the Quasi-War thus vindicated the Federalist foreign-policy theory. Weakness had invited insults. Restoring domestic tranquility—peace, prosperity, and national honor—required a vigorous common defense. And oceans provided little protection for a republic in a world of imperial sea powers. That these principles were essential elements of the Federalist platform at the ratification conventions, and thus indelible parts of our Constitution, did not guarantee they would guide U.S. policy. Throughout American history, in fact, harassment and humiliation have prompted American leaders to recall and apply the Federalists’ prescriptions.

Today, after decades of war, U.S. policymakers are contemplating force reductions and defense-spending cuts. This buildup-drawdown cycle is a familiar exercise in American history. After the naval expansion that ended the Quasi-War, the United States under Democratic-Republican direction retained only a skeletal military. Owing to Jefferson’s distaste for the expense of the navy and his anxiety over a standing army, his administration saw the navy reduced to fewer than twenty seaworthy warships and an ill-trained army spread thin across the frontier.[78] Jefferson recognized the strategic risk he was bequeathing his successor, writing to Madison in 1809, “I know no government which would be so embarrassing in wars as ours.”[79]

Britain took notice, seizing the chance to again contest U.S. rights of neutrality, impress American sailors, and finally, to invade the country in 1812. During the ratification debates, few had advocated more stridently than Madison for the national government’s power to raise and support military establishments. Yet President Madison seemed to have forgotten what delegate Madison knew well: weakness invites hostility. Britain’s invasion apparently reminded Madison of what ratification had decided. Incensed by the poor performance and insubordination of state militias at the war’s outset, he urged Congress to create “those large and permanent military establishments” the Constitution permits, his supporters fear, and without which the nation may fall.[80] The course of the war only strengthened his conviction. “Experience has taught us,” or reminded Madison anyhow, “that a certain degree of preparation for war is . . . the best security for the continuance of peace.” He again implored Congress to “provide for the maintenance of an adequate regular force.”[81]

Today, as many in the foreign policy community once again aspire to “right-size” our armed forces,[82] the Federalist position reminds us that military readiness may only seem expensive until we have to reckon with the price of underinvestment, whether it be a blockaded trade route or an outright invasion. Moreover, downsizing and disarmament on our part does not necessarily induce reciprocal behavior from our adversaries. At the Constitutional Convention, when soon-to-be Anti-Federalist Elbridge Gerry moved to add a provision limiting the new federal army to 3,000 soldiers, Washington allegedly gave his assent, conditional on the passage of a companion motion: “no foreign enemy should invade the United States at any time, with more than three thousand troops.”[83] These Federalist insights—that weakness is provocative and that happiness at home depends on strength abroad—remain as relevant today as they were in the 1780s.

Even more relevant at present than it was at the Founding is the Federalists’ understanding of geography. While Anti-Federalists conceived of oceans as protective moats that made geopolitical isolation possible, Federalists saw oceans as arenas of commercial and military competition that they could not evade. The Quasi-War and War of 1812—where enemy vessels dotted the eastern seaboard and trade wars played out across the North Atlantic—vindicated the Federalist view. Today, the president is not wrong to note that we have “a big, beautiful [o]cean” that helps shield us from surprise, large-scale attacks.[84] Yet if the ocean could not prevent harassment or even invasion in the age of sail, we can hardly expect it to deter adversaries in an era of vulnerable sea-based supply chains, amphibious warfare, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and cyberattacks. From Pearl Harbor to 9/11, American reliance on the stopping power of water has proven foolish.

American Expansion and Consolidation Reflects the Federalist Vision

Post-ratification U.S. history has not only vindicated the Federalists’ foreign-policy prescriptions. In important respects, the nation’s history also reflects the Federalists’ theory of preserving American exceptionalism through enlargement and consolidation.[85] From Florida to Alaska, the United States incorporated new states into the Union; from Guam to Puerto Rico, it brought new citizens into its orbit.

The Federalists contended that preserving American exceptionalism required rendering the world, especially the Western and Northern Hemispheres, hospitable to republicanism. This would be accomplished, in part, by bringing new territory into the republic’s orbit. This theory of preservation through expansion was articulated in The Federalist Papers and would later find expression in historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis.”[86]

But the theory perhaps owes its genesis, and certainly its implementation, to Thomas Jefferson. Commonly misunderstood for his later leadership of the Democratic-Republican Party, Jefferson was an early champion of ratification (while also pressing for a bill of rights).[87] It was Jefferson who first envisioned an American-created “empire of liberty”—a proto-Monroe Doctrine—in 1780, years before America had even won its independence.[88] “The day is not distant,” Jefferson wrote in 1820, “when we may formally require a meridian of partition through the ocean which separates the two hemispheres, on the hither side of which no European gun shall ever be heard.”[89] For Jefferson, the empire of liberty was no mere abstraction. It meant regional ascendency, but also enlargement and consolidation of the Union. Jefferson made good on his goal, of course, through the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, nearly doubling the Union’s size by extending its western boundary from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains.

But Jefferson’s plan for the empire also pushed northward. In his first invocation of the phrase in 1780, he wrote, “we shall form to the American union a barrier against the dangerous extension of the British Province of Canada, and add to the empire of liberty an extensive and fertile country, thereby converting dangerous enemies into valuable friends.”[90] Later writing to the newly inaugurated President Madison, Jefferson again urged bringing Canada under America’s banner (advice that must have appeared prescient once Madison’s executive mansion was burned by a British army that invaded via Canada). “We consider their [Canadians’] interests the same as ours,” Jefferson wrote, “and the object of both must be to exclude all European influence in this hemisphere.”[91] Neither Jefferson, Madison, nor their predecessors, of course, would succeed in erasing that “artificially drawn line” that continues to vex presidents to this day.[92]

The Federalists’ case for enlarging and consolidating the American orbit echoes still today in discussions about acquiring additional American territory. Making Canada the “fifty-first state,” annexing Greenland, or reclaiming the Panama Canal—each proposed by the current U.S. administration—might have been what Hamilton hoped for when he envisioned an America that would “dictate the terms of the connection” between the hemispheres.[93] Debate over whether and how such acquisitions might occur, however, obscures just how successful the Federalist foreign-policy vision has been. Behind the Federalists’ hope for establishing an empire of liberty was the need to buffer the Union from hostile regimes. Today, Canada, Greenland, and Panama are all republics and longtime U.S. allies, thanks in large part to the success of the Federalist vision. Through Jefferson’s Declaration and the Federalists’ Constitution—documents imported and imitated across the world—as well as the prudent projection of American power and goodwill, the United States has “convert[ed] dangerous enemies into valuable friends.”[94] In ways likely unimaginable to the Founders, the United States has established and enlarged the empire of liberty, making the world safe for its republican form of government.

Conclusion

But no empire lasts forever. The empire of liberty is coming under increasing strain as America’s adversaries grow stronger, bolder, and more aligned. And there are those in the United States who doubt that this empire is worth defending. It is therefore a fitting time to revisit the Federalists’ foreign-policy vision that gave rise to it. If the Federalists’ theory of preservation through expansion and consolidation has merit, then retrenchment from the empire of liberty will not only sacrifice the country’s ability to shape the world to its favor; it will also imperil the project of republican self-government at home.

Each generation must apply its own theory of national self-preservation. But faithful adherence to the U.S. Constitution demands that we at least remember the foreign-policy theory espoused by the Federalists and ratified by an act of popular sovereignty. By ratifying the Constitution, Americans endorsed the Federalists’ contentions: that domestic tranquility required a robust common defense, that external threats imperiled the republic’s survival more than internal ones, and that America would only endure by making the world hospitable to its republican form. Stridently and often cogently, the Anti-Federalists disputed each of these claims, and Americans adopted the Constitution over their objections. We honor their choice when we recall and apply the Federalists’ foreign-policy vision for “preserving and protecting the principles of republicanism.”[95]

Luke J. Schumacher is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics at the University of Virginia and a non-resident fellow of Columbia Law School’s National Security Law Program. Previously, he was a U.S. Army intelligence officer who served in Afghanistan, across the Indo-Pacific region, and elsewhere. He holds a B.S. from West Point, an M.Phil. from the University of Cambridge, and J.D. from Stanford Law School, and is an alumnus of the Stanford AHS chapter.

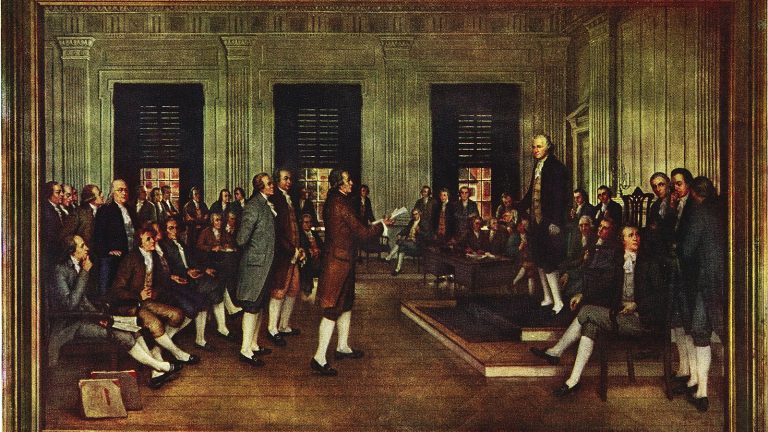

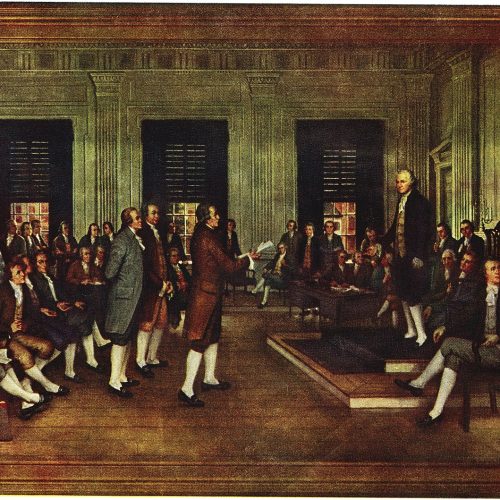

Image: ‘The Adoption of the U.S. Constitution in Congress at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Sept. 17, 1787’ (1935), by John H. Froehlich.jpg, Dec. 31,1935, from John F. Froehlich. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27The_Adoption_of_the_U.S.Constitution_in_Congress_at_Independence_Hall,_ Philadelphia,_Sept._17,_1787%27%281935%29,_by_John_H._Froehlich.jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Brutus, “Letter No. 1,” October 18, 1787, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/brutus-i.

[2] James Madison, “Federalist10,” in The Federalist Papers, eds. Clinton Rossiter and Charles R. Kesler (New York: Signet Classic, 2003), 71–79.

[3] James Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution” at the Virginia Ratification Convention, June 6, 1788, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-11-02-0062.

[4] “Thomas Jefferson to George Rogers Clark, December 25, 1780,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0295.

[5] Patrick Henry, “Speech Before Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/patrick-henry-virginia-ratifying-convention-va.

[6] Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist 15,” in The Federalist Papers, 101.

[7] Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (New York: Knopf, 2000), 453-56.

[8] See John Jay’s report to Congress, John Adams’s reply, and the British foreign secretary’s correspondence in Secret Journals of the Acts and Proceedings of Congress, from the First Meeting Thereof to the Dissolution of the Confederation, 4 vols. (Boston: Thomas B. Wait, 1820), 4:185-287, https://archive.org/details/secretjournals04unit/page/184/mode/2up; John Jay, “Jay to John Adams,” November 1, 1786, in The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay,ed. Henry P. Johnston, 4 vols. (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1890-93), 3:214-15, available at https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/johnston-the-correspondence-and-public-papers-of-john-jay-vol-3-1782-1793.

[9] John Jay, “Federalist 4,” in The Federalist Papers, 41.

[10] “Introduction to the Ratification of the Constitution in Georgia,” in The Documentary History of the Ratification Digital Edition, ed. John P. Kaminski et al. (University of Virginia Press, 2009) [hereinafter Documentary History of the Ratification], https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/default.xqy?keys=RNCN-print-02-03-02-0003-0001.

[11] Edward Rutledge, “Speech in the South Carolina House of Representatives,” January 16, 1788, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/sc_rutledge.pdf. See also Marshall Smelser, “Whether to Provide and Maintain a Navy (1787-1788),” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 83, no. 9 (Sept. 1957), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1957/september/whether-provide-and-maintain-navy-1787-1788.

[12] Hugh Williamson, “Speech at Edenton, N.C.,” February 26, 1788, in Documentary History of the Ratification, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/nc_williamson.pdf.

[13] James Madison, “Weakness of the Confederation” at the Virginia Ratification Convention, June 7, 1788, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-11-02-0065. See also Luke J. Schumacher, “A Council of Grand Strategists: The Original Hope, Fear, and Intent of the U.S. Senate in Foreign Affairs,” working paper, available at https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5006658, 12-14.

[14] Oliver Ellsworth, “A Landholder” No. 2, November 12, 1787, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/a-landholder-ii/.

[15] Oliver Ellsworth, “A Landholder” No. 1, November 5, 1787, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/a-landholder-i/.

[16] John Jay, “An Adress to the People of the State of New York on the Subject of the Constitution,” c. April 12, 1788, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jay/01-04-02-0324.

[17] Samuel Flagg Bemis, Pinckney’s Treaty: America’s Advantage from Europe’s Distress, 1783-1800, rev. ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1960), chaps. 2-3.

[18] “One of Four Thousand,” October 15, 1787, The American Founding, https://americanfounding.org/entries/one-of-four-thousand.

[19] Newport Herald, October 25, 1787, quoted in Norman A. Graebner, “Isolationism and Antifederalism: The Ratification Debates,” Diplomatic History 11, no. 4 (1987): 338.

[20] Charles Pinckney, June 25, 1787, in The Records of the Federal Convention, ed. Max Ferrand (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1911—1937), 4 vols. [hereinafter Records], 1:402. (Unless otherwise indicated in parentheses, citations to the Records are to James Madison’s notes.) The records here do not specify whether the speaker was General Charles Cotesworth Pinckney or instead the general’s cousin of the same name who also represented South Carolina.

[21] Alexander Hamilton, June 29, 1787, in Records, 1:467.

[22] Nathan Tarcov, “The Federalists and Anti-Federalists on Foreign Affairs,” Teaching Political Science 14, no. 1 (1986): 38-45.

[23] Brutus, “Letter No. 7,” January 3, 1788, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/brutus-vii.

[24] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788.

[25] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788.

[26] Madison, “Weakness of the Confederation.”

[27] Edmund Randolph, “Speech in the Virginia Convention,” June 6, 1788, in Documentary History of the Ratification, https://archive.csac.history.wisc.edu/Edmund_Randolph_Speech_in_the_Virginia_Convention.pdf.

[28] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[29] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 9, 1788, in The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, 5 vols., ed. Jonathan Elliot (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1896) [hereinafter, The Debates], vol. 3, available at Online Library of Liberty, Liberty Fund, https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/elliot-the-debates-in-the-several-state-conventions-vol-3.

[30] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788.

[31] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 9, 1788.

[32] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788.

[33] A Plebian, “An Address to the People of New York,” April 17, 1788, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/a-plebeian-an-address-to-the-people-of-new-york. See also “Vine and Fig Tree,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/vine-and-fig-tree.

[34] Federal Farmer, “Letter No. 1,” October 8, 1787, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/federal-farmer-i.

[35] To borrow from Bismarck’s critique of preventive war. See Bismarck quoted in Scott A. Silverstone, “Haunted by the Preventive War Paradox,” Military Strategy 5, no. 2 (Spring 2016): 17–21.

[36] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788. Defending powers, see, inter alia, Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist 23” and “Federalist 34,” and James Madison, “Federalist 41,” in The Federalist Papers, 149, 203, 253.

[37] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution,” referencing U.S. Constitution, art. 1, sec. 8, cl. 15.

[38] James Madison, “Federalist 46,” in The Federalist Papers, 296; see also Madison, “Federalist 45,” in The Federalist Papers, 288.

[39] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[40] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[41] James Madison, “The Power to Levy Direct Taxes: The Mississippi Question” at the Virginia Convention, June 12, 1788, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-11-02-0076.

[42] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[43] George Washington, “Fifth Annual Address to Congress,” December 3, 1793, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/fifth-annual-address-congress.

[44] John Jay, “Letter to Congress,” May 8, 1786, https://dlc.library.columbia.edu/jay/ldpd:31656.

[45] James Wilson, “Speech at a Public Meeting,” October 6, 1787, in The Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Antifederalist Speeches, Articles, and Letters During the Struggle Over Ratification, ed. Bernard Bailyn (New York: Library of America, 1993), 65–66.

[46] Christopher Gore, “Convention of Massachusetts,” January 22, 1788, in The Debates, vol. 2, available at Online Library of Liberty, Liberty Fund, https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/elliot-the-debates-in-the-several-state-conventions-vol-2.

[47] Jusserand quoted in Gregory Mitrovich, “History Lessons: Five Myths about America’s Rise,” The National Interest, April 2, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/history-lessons-five-myths-about-americas-rise-181768.

[48] Brutus, “Letter No. 7.”

[49] Thompson quoted in “Newspaper Report of the Massachusetts Ratification Convention,” January 23, 1788, Constitutional Sources Project, Quill Project, https://www.consource.org/document/newspaper-report-of-the-massachusetts-ratification-convention-1788-1-23.

[50] Grayson, “We have been told of Phantoms Speech” at Virginia ratifying convention, June 11, 1788, available at https://constitution.org/1-Constitution/afp/borden02.htm.

[51] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[52] Federalist, no. 41 (James Madison) , 257.

[53] Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist 9,” in The Federalist Papers, 68.

[54] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[55] Henry, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 5, 1788.

[56] George Mason, “Virginia Ratifying Convention,” June 4, 1788, The Founder’s Constitution, https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch8s37.html.

[57] See, e.g., Alexander Hamilton, June 18, 1787 in Records, 1:308 (Alexander Hamilton’s notes); Gouverneur Morris, July 7, 1787, in Records 1:553; James Madison, June 17, 1787, in Records, 1:285-86; Madison & Hamilton, “Federalist19,” in The Federalist Papers, 128-29; Randolph, “Speech in the Virginia Convention,” June 6, 1788; Oliver Ellsworth, “Speeches in the Connecticut Convention,” June 4, 1788, Teaching American History, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/oliver-ellsworth-and-william-samuel-johnson-speeches-in-the-connecticut-convention.

[58] John Jay, “Federalist 1,” in The Federalist Papers, 31.

[59] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[60] Federalist, no. 9 (Alexander Hamilton), 67.

[61] Federalist, no. 9 (Alexander Hamilton), 66.

[62] James Madison, “Vices of the Political System of the United States, April 1787,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-09-02-0187.

[63] Gouverneur Morris, July 7, 1787, in Records, 1:552. See also Records, 1:285, 1:320, 1:323, 1:328, 1:360, 1:451, 2:48, 2:53, 2:452, 3:53, 3:131, 3:301.

[64] Alexander Hamilton, “Federalist 11,” in The Federalist Papers, 85-86.

[65] See Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2006), chap. 1.

[66] Madison, “Weakness of the Confederation.”

[67] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”

[68] Federalist, no. 9 (Alexander Hamilton), 67.

[69] Washington, “First Annual Address to Congress,” January 8, 1790, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/first-annual-address-congress-0.

[70] Lt. Cdr. David B. Stansbury, “The Quasi-War with France,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 6, no. 3 (Sept. 1992), https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/1992/september/quasi-war-france.

[71] Washington, “Proclamation 4—Neutrality of the United States,” April 22, 1793, The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/proclamation-4-neutrality-the-united-states-the-war-involving-austria-prussia-sardinia. See also Act of June 5, 1794 (Neutrality Act of 1794), ch. 50, 1 Stat. 381, available at https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/1/STATUTE-1-Pg381.pdf.

[72] Stansbury, “The Quasi-War with France.”

[73] Stansbury, “The Quasi-War with France.”

[74] John Adams, “Message to the Senate,” May 31, 1797, https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/ja97-04.asp?.

[75] Monticello Library Staff, “XYZ Affair,” Monticello — Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, 2008, https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/xyz-affair/.

[76] Rep. Robert Goodloe Harper quoted in Monticello Library Staff, “XYZ Affair.”

[77] Stansbury, “The Quasi-War with France.”

[78] Nathan Miller, The U.S. Navy: A History, 3rd ed (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 45–46; David Alan Martin, “Mr. Jefferson’s Army in Mr. Madison’s War: Atrophy, Policy, and Legacy in the War of 1812” (Master’s Thesis, University of Southern Mississippi, 2016), https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/204/; Leonard D. White, The Jeffersonians: A Study in Administrative History, 1801–1829 (New York: Macmillan, 1951).

[79] Thomas Jefferson quoted in Charles Edel, “Extending the Sphere: A Federalist Grand Strategy,” in Rethinking American Grand Strategy, ed. Elizabeth Borgwardt, Christpoher McKnight Nichols, and Andrew Preston (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 101.

[80] James Madison, “Annual Message to Congress,” November 4, 1812, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/03-05-02-0334.

[81] James Madison, “From James Madison to Congress,” February 18, 1815, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/03-08-02-0523.

[82] See Jennifer Kavanaugh, “The US Army Is About to Get Smaller, Especially in Europe,” Responsible Statecraft, April 15, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/us-army-troops-budget; David A. Deptula, “President Trump Decreased U.S. Defense Budgets, Here’s The Real Impact,” Forbes, July 16, 2025, https://www.forbes.com/sites/davedeptula/2025/07/16/why-president-donald-trump-might-increase-americas-defense-budget/.

[83] Gerry, August 18, 1787, in Records, 2:329; “George Washington Anecdote,” Teaching American History, August 18, 1787, https://teachingamericanhistory.org/document/george-washington-anecdote/. See also Federalist, no. 41 (James Madison), 253.

[84] Donald J. Trump [@realDonaldTrump], X, February 19, 2025, https://x.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1892242622623699357; “President Trump Remarks at Future Investment Initiative Priority Summit,” C-SPAN, February 19, 2025, at 00:58:15, https://www.c-span.org/program/white-house-event/president-trump-remarks-at-future-investment-initiative-priority-summit/655974.

[85] Edel, “Extending the Sphere: A Federalist Grand Strategy.”

[86] Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” Address to the American Historical Association, July 12, 1893, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22994/22994-h/22994-h.htm.

[87] See, inter alia, Jefferson’s letters (each available at Founders Online, National Archives): to James Madison, December 20, 1787, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0210; to James Madison, February 6, 1788, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0601; to George Washington, May 2, 1788, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-13-02-0059; to Edward Carrington, May 27, 1788, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-13-02-0120; and to George Washington, December 4, 1788, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-14-02-0111.

[88] Dexter Perkins, The Monroe Doctrine, 1823-1826 (Harvard University Press, 1927), 100.

[89] “Thomas Jefferson to William Short,” April 13, 1820, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/56035/56035-h/56035-h.htm.

[90] “Thomas Jefferson to George Rogers Clark,” December 25, 1780.

[91] “Thomas Jefferson to James Madison,” April 27, 1809, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-01-02-0140.

[92] Donald Trump quoted in Alys Davies and Mike Wendling, “Trump Ramps up Threats to Gain Control of Greenland and Panama Canal,” BBC News, January 8, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4gzn48jwz2o.

[93] Federalist, no. 11 (Alexander Hamilton), 86.

[94] “Thomas Jefferson to George Rogers Clark,” December 25, 1780.

[95] Madison, “General Defense of the Constitution.”