1776: The Beginnings of American Exceptionalism Abroad

The Religious Republic: America’s Statecraft Under God

Share On:

Inviting Quebec to join America’s resistance to Parliament in 1774, the Continental Congress invoked the union between the Swiss Cantons’ Roman Catholic and Protestant states, which “living in the utmost concord and peace” helped defy “every tyrant that has invaded them.”[1] The next year, Congress declared “the fate of the protestant and catholic colonies to be strongly linked together, and [we] therefore invited you to join with us in resolving to be free.”[2] Not taking no for an answer—the invitation was disingenuous anyway—an army of Protestant colonials marched north to conquer Canadian Catholics into liberty.

On the eve of that invasion, one thousand men of the Continental Army gathered for a sermon at First Presbyterian Church in Newburyport, Massachusetts, where the Great Awakening’s George Whitefield—who in life warned of linkage between Roman Catholic power and the British Parliament—lay buried beneath the tiles. Then those Protestant soldiers did the most un-Protestant thing imaginable. Prying the crypt to behold Whitefield’s corpse, they stripped his Anglican collar and wristbands and distributed them as relics for the campaign.[3]

Judging from the words and deeds of these curious colonials, religion influenced early American foreign relations. But does it matter to us, 250 years later, if Americans mixed religion and statecraft in their earliest diplomacy? Do we carry their relics, those heirlooms of belief deposited in the foundation of our country? I will argue that it does matter, and we do carry them. In fact, the religious record of the American republic solves the riddle of American identity: what makes America great? But to know the answer, we must enter the minds of our colonial and revolutionary forebears and read American diplomatic and constitutional history in a metaphysical mode. For that, we must commit political theology.

Politics, like religion, is ritualistic. Both organize public life through ceremony and symbolism. Political theology is an account of how the rituals, ideas, and authority claims of politics and religion blend into, reinforce, and qualify each other. Alexis de Tocqueville observed, “Next to each religion is a political opinion that is joined to it by affinity . . . Allow the human mind to follow its tendency and it will regulate political society and the divine city in a uniform manner; it will seek, if I dare say it, to harmonize the earth with Heaven.”[4] Anglican theologian Oliver O’Donovan echoes and elaborates Tocqueville’s point:

Shall we conclude, then, that within every political society there occurs, implicitly, an act of worship of divine rule? . . . For without the act of worship political authority is unbelievable, so that binding political loyalties and obligations seem to be deprived of any point. The doctrine that we set up political authority, as a device to secure our own essentially private, local and unpolitical purposes, has left the Western democracies in a state of pervasive moral debilitation, which, from time to time, inevitably throws up idolatrous and authoritarian reactions.”[5]

What distinguishes the American Revolution from secular revolutions later is that America undertook its war for independence “under God.” American men of state—whatever their private religious devotion—publicly recognized and appealed to a higher authority that rules the destiny of nations. They rejected the doctrine that “we the people” set up political authority outside divine rule. Russell Kirk said, “It is one of the great premises of American political theory that all just authority comes from the people, under God . . . [America’s early statesmen] did not believe that the voice of the people is the voice of God.”[6]

Styled alternately by scholars as Hebraic or Christian Republicanism, this political theology resonated deeply with Americans due to its fusion of biblical and classical authorities.[7] America’s political theology rested on two pillars. First, natural rights derived ultimately from the God of the Bible, and God alone was king. Second, the Bible modeled covenantal relations between ruler and ruled that limited and threatened the ruler’s authority if violated. In short, Kirk continues, “the only legitimate kings who could rule absolutely were God and Jesus; everyone else needed the consent of the people.”[8]

Religion provided America’s protagonists standards of reason, morality, justice, and purpose in each episode of the revolutionary drama. These standards demanded that the actors justify themselves for history’s script. The record of sermons, state papers, political pamphlets, and newspaper editorials shows that the drama climaxing in American independence had religious set-pieces staged by all sides for political purposes. These spanned political disputes over Protestant England’s foreign policy, biblical debates over monarchy, and geopolitical reckoning over the constitution of post-Reformation Europe.

We will survey three episodes where American religion, statecraft, and constitutional politics intersected: first, the British Imperial Crisis (1763-1775), where Britain seemed to betray the Protestant cause of political and religious liberty; second, the debate over monarchy and the presidency (1776 and 1787), where the Bible shaped perceptions of the legitimacy of kingship; third, the achievement of federal union (1787-1789), where post-Reformation federative experiments furnished a vision for solving the geopolitical threat to America.

The focal question American leaders faced when they decided to fight to replace Britain’s imperial governance was how to protect and safeguard their thirteen republics in a world of ravenous monarchical empires. American leaders answered with a great experiment, a continental federal republic, and “part of the answer—a large part—came from Protestant history and doctrine.”[9] America’s foreign relations have these Protestant roots that grew in the soil of religious republicanism.[10]

To be sure, failed Anglo-American imperial relations—rather than religion—triggered the war, as the Declaration of Independence testifies. The failure of either side to accept a reformed imperial-federal constitution exploded the British Imperial Crisis that had simmered since 1763.[11] But the Declaration elides the crisis’s religious sources; they are clear when examining the petitions and declarations of colonial congresses in the 13 years preceding 1776.[12]

In the fires of this Protestant faith, the Founders forged a trident of foreign policy principles: moralism, republicanism, and internationalism. This chapter will analyze how Americans considered statecraft to be “under God” and, from this Protestant legacy of religious republicanism, suggest implications for foreign policy hands today about the nature of our government.

The Genesis of American Political Theology

To focus first on the Revolution would be to enter the action in medias res and miss the genesis of America’s political theology.[13] Protestant religion—the overwhelming faith of British Americans—was enmeshed in colonial America’s way of life, where threats to religious liberty were indistinguishable from threats to liberty as such. Since 1607, America was settled as a Reformation Protestant society that knew no Counter-Reformation, and its experience of self-government, religious freedom, economic opportunity, and territorial growth were inseparable.[14]

Unlike Protestants in Europe, and specifically England, who experienced the swings of consolidation and backlash to the Protestant cause, colonial Americans had no need to accommodate an opposing establishment in the name of domestic or international peace. As the British Parliamentarian Edmund Burke said:

The people are Protestants; and of that kind which is the most adverse to all implicit submission of mind and opinion. This is a persuasion not only favorable to liberty, but built upon it. . . . Their very existence depended on the powerful and unremitted assertion of that claim. All Protestantism, even the most cold and passive, is a sort of dissent. But the religion most prevalent in our Northern Colonies is a refinement on the principle of resistance; it is the dissidence of dissent, and the Protestantism of the Protestant religion.[15]

Allied to this political theology was a view of Britain as a bulwark of the Protestant cause of liberty. For English Protestants, religion and foreign policy were deeply intertwined since the pope had absolved the allegiance of English Catholics, adding a domestic threat of subversives and assassins to the foreign threat of Catholic Spain.[16] After Spain’s defeat, England locked into a protracted conflict with Catholic France that alternated for decades between hot war, cold war, and détente.[17] The post-Reformation state system of Europe—wracked by rivalries among religiously inspired monarchies jockeying for commerce and empire—played out in the third world, North America, where British American Protestants were the front line.

Thus, English Protestantism, mixing love of liberty with a crusading spirit against Catholic hegemony, inflected the foreign policy of the Anglophone world with a distinct moralism. Albion’s moralism was inherited by Albion’s seed, as Americans, like the British, “saw their struggles as wars against an evil empire”—even if that empire later centered in London.[18]

This moralism secularized religion and sacralized politics, giving colonial Americans concepts of world order that owed much to Protestant visions of liberty.[19] For example, John Adams observed to John Jay in 1785, “the increasing Liberality of Sentiment among Philosophers and Men of Letters, in various Nations, has for Sometime given Reason to hope for a Reformation, a Kind of Protestantism, in the Commercial System of the World.”[20] In 1800, Benjamin Rush predicted to Thomas Jefferson, “It is only necessary for republicanism to ally itself to the Christian religion to overturn all the corrupted political and religious institutions in the world.”[21]

Thus, when the Revolution came and hegemonic Britain became in the eyes of Americans the successor evil empire to France and Spain, even while “many colonial patriots interpreted their struggle in Protestant terms and others in secular terms, all patriots made America itself a sort of religion.”[22] America inherited Britain’s title as Protestant bulwark of the cause of liberty.

However, none of America’s Protestant moralism precluded adroit cooperation with Catholic France and Spain in an expedient republican realpolitik, which recognized world realities.[23] With an independent foreign policy, America turned to these vanquished Catholic empires as allies of convenience against Britain. Still, it was a scandalizing turnabout. Loyalists howled. Even Patriots harbored reservations about the effect of the alliance on Europe’s balance of power boomeranging to America. John Dickinson jotted that “France must rise on [Britain’s] Ruins. Her Ambition. Her Religion. Our danger from thence. We shall weep at our victories.”[24]

The spirit of English Protestant settlement in America unified the material and the spiritual, so that political and religious liberty were joined. It unleashed energies for a culturally English Protestant national project.[25] This Protestant exceptionalism sired an early national exceptionalism, the belief that America was a chosen nation for an almost-chosen people.[26] Even as the colonies pluralized religiously, their pluralism was within a Protestant exceptionalism that could be tapped, as a reservoir of individual and corporate purpose, for great endeavors.[27]

The Legacy of the Seven Years’ War, Imperial Crisis: 1763-1775

The Imperial Crisis is the first episode we will consider when religion shaped pre-revolutionary America’s statecraft and constitutional politics by directing American moralism against Great Britain. The debate over Parliament’s authority in the Imperial Crisis originated in the Seven Years’ War that ended in 1763 in victory and yet, inexplicably to the colonists, in an unjust peace. The ideological demands of this war fused colonial identity, Protestant exceptionalism, and millennial expectation, transforming colonial America.[28] Between 1763 and 1775, three sparks lit that long fuse: the Royal Proclamation in 1763, the so-called “Bishop’s Plot,” and the Quebec Act of 1774.

Victory in the Seven Years’ War heralded an “end of history” of sorts for the colonies, in the triumph of Anglo-Protestant power and its unrivaled dominion over the continent. The Catholic empires of France and Spain were vanquished and relegated to North America’s periphery, and their Indian allies were humbled. The 1763 Peace of Paris recognized Britain’s preponderant power in the New World and upended Europe’s balance of power in its favor.[29] But the peace augured trouble for a British Empire that gained Catholic possessions in formerly French Canada. In retrospect, the conquest of Canada in the Seven Years’ War sparked a crisis over the very nature of the empire.

Americans had a rude awakening when the Royal Proclamation of 1763 limited westward expansion into Indian territory and organized British Canada with toleration of Roman Catholicism. These reforms, meant to appease Britain’s new Indian and French subjects, made Parliament appear like turncoats to Americans.[30] Worse, they revealed that Parliament viewed its authority to govern New World possessions more expansively than the colonies did, which saw these acts as a political challenge to settled relations under the English constitution.[31]

After the Royal Proclamation, the so-called “Bishop’s Plot” reinforced colonial suspicions that Anglican Britain was the tyrannical successor to papist France and Spain. In the mid-1760s and again in the early 1770s, Church of England clergymen lobbied Parliament passionately for the establishment of an American Anglican bishop.[32] This spooked dissenting Protestants, who aimed rhetorical cannons on the English and Anglican church that had, until recently, been trained on the French and Catholic church.[33]

These colonial Protestants feared that if Parliament could create dioceses and appoint bishops, they could collect tithes (taxes) and crush (their) heresy.[34] John Adams recalled that “apprehension of Episcopacy contributed . . . as much as any other cause to arouse the attention not only of the inquiring mind, but of the common people, and urge them to close thinking on the constitutional authority of the parliament over the colonies.”[35]

Below the surface raged a culture war between Presbyterians, Congregationalists, and Anglicans over whether an established and influential Anglican Church threatened religious liberty. An American Anglican bishop symbolized this fear.[36] Historian Bernard Bailyn said that it “brought into focus a cluster of ideas, attitudes, and responses alive with century-old Popish-Stuart-Jacobite associations that would enter directly into the revolutionary controversy in such writings as John Adams’ Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law (1765).”[37]

For the simmering Imperial Crisis, an accidental but important legacy of the “Bishop’s Plot” was the creation of a network of Loyalist Anglican ministers, originally to lobby for the episcopal appointment, who agreed to monitor the press and publish rebuttals to Patriot propaganda.[38] That network included Samuel Seabury, who provided “the most comprehensive and sustained polemical effort by any doctrinaire Tory to repudiate the pre-revolutionary movement, demolish its constitutional arguments, discredit its methods of protest, and expose its coercive tactics and presumptions.”[39] Seabury’s writings provoked a precocious sophomore at King’s College to take up his pen for the revolution. Alexander Hamilton exploded onto the scene in articles arguing that Parliament was resurrecting Catholic tyranny in North America with the Quebec Act.

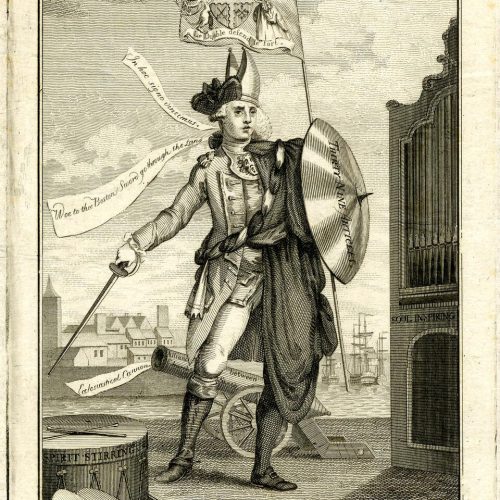

Figure 1. Capturing the revulsion among Protestant New Englanders, Paul Revere republished a cartoon titled “The Mitred Minuet” of bishops dancing around the Quebec Act to the approval of parliamentary ministers including Lord North, standing beneath a flying Devil.[40]

In 1774, Parliament’s Quebec Bill heated the simmering crisis to a rolling boil. Extending Quebec’s boundaries to include all western lands north of the Ohio River, the Act retained Canada’s French civil law and established the Roman Catholic Church there. This, with the Royal Proclamation’s land grant restrictions on American colonists, summoned the very specter of which George Whitefield had warned: Parliament backing Roman Catholic power over Protestants.

Suspicions of Anglican collusion with Rome estranged Americans from Parliament, accelerating a constitutional conflict. Many colonists perceived a plan by Parliament to promote Roman Catholicism in America and accused Parliament of depriving British subjects in Canada of liberty under English law and of encircling Protestant America with a popish noose.[41]

The Continental Congress in 1774 vilified parliamentary ministers “unfriendly to the protestant cause, and inimical of liberty,” and appealed to the king in the name of the Glorious Revolution, when England secured a Protestant constitutional monarchy: “we were born the heirs of freedom, and ever enjoyed our right under the auspices of your royal ancestors, whose family was seated on the British throne, to rescue and secure a pious and gallant nation from the popery and despotism of a superstitious and inexorable tyrant.”[42]

The young Hamilton amplified these complaints against the king’s ministers in Parliament. With all the passion of an undergraduate, he accused the bulwark of Protestant liberty in Europe of betraying the cause in North America:

Does not your blood run cold, to think that an English Parliament should pass an act for the establishment of arbitrary power and Popery in such an extensive country? . . . If they had been friends to the Protestant cause, they would never have provided such a nursery for its great enemy; they would not have given such encouragement to Popery. . . They may as well establish Popery in New York, and the other colonies, as they did in Canada. They had no more right to do it there than here.”[43]

Showing an early knack for geopolitics, the twenty-something Hamilton argued that the Quebec Bill was a containment policy, because “[It] will attract droves of emigrants from all the Roman Catholic States in Europe, and these colonies, in time, will find themselves encompassed with innumerable hosts of neighbors, disaffected to them, both because of difference in religion and government.”[44]

Certain of an evil conspiracy by parliamentary elites, Hamilton concluded that “this act develops the dark designs of the ministry more fully than any thing they have done, and shows that they formed a systematic project of absolute power.”[45] To what end? None greater than that which a Protestant could conceive: Counter-Reformation! Hamilton catastrophized, “should it ever comport with the designs of an ambitious and wicked minister, we may see an Inquisition erected in Canada, and priestly tyranny hereafter find as propitious a soil in America as it ever has been in Spain or Portugal.”[46] Staging Protestant set-pieces to rouse populist passions, Hamilton early on exemplified the paranoid style in American politics.

The Bible, Monarchy, and the American Presidency: 1776 and 1787

The second episode where religion shaped American statecraft and constitutional politics was the debate over the legitimacy of kingship, following publication in 1776 of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. Paine resurrected English Civil War-era republican and biblical arguments against kingship and, according to historian Walter McDougall, “tapped both the vocabularies Americans knew—country-party ideology and moral evangelism—to call for separation from Britain.”[47] Paine’s thesis was that kingship is “a form of government which the word of God bears testimony against, and blood will attend it.”[48] Common Sense moved colonists to reject kingship itself as idolatrous and fused the revolutionary cause with republicanism, a prong of America’s foreign policy ever since.

Before Common Sense, colonial petitions and continental congresses appealed to the king against his ministers—they wanted more monarchy, not less.[49] For example, the Continental Congress in its address to the people of Great Britain blamed a “ministerial plan of enslaving your fellow subjects in America.”[50] Before Paine, the fear was that ministers and favorites of the king—a headless fourth branch of government you might call the empire’s administrative state—were conspiring to subvert American liberty behind his back: “a kind of fourth power that the constitution knows nothing of, or has not provided against. . . which absolutely controls the king, Lords, and Commons.”[51] After Paine’s Common Sense, the fear became religious and colonists took a hard turn against kingship itself.

In the tract, Paine envisions America as a Protestant promised land and draws geopolitical and theological implications for its foreign policy. He writes, “the Reformation was preceded by the discovery of America, as if the Almighty graciously meant to open a sanctuary to the persecuted in future years, when home should afford neither friendship nor safety.”[52] Beyond the geopolitical case for independence, Paine made a radical theological case against America’s submission to royalty.

Going to Hebraic Republicanism’s first principles—where God alone is king—Paine asks, “But where, says some, is the King of America? I’ll tell you, friend, he reigns above, and doth not make havoc of mankind like the Royal of Britain.”[53] Paine then launches a republican reading of Scripture on political authority:

As the exalting of one man so greatly above the rest cannot be justified on the equal rights of nature, so neither can it be defended on the authority of scripture; for the will of the Almighty, as declared by Gideon and the prophet Samuel, expressly disapproves of government by kings. All anti-monarchical parts of scripture have been very smoothly glossed over in monarchial governments, but they undoubtedly merit the attention of countries which have their governments yet to form.[54]

Paine’s use of Scripture was electric and wrought a profound change in the minds of Americans about their king. He pushed beyond Americans’ earlier presumption that all they needed was King George to bring Parliament to heel. In the words of historian Eric Nelson, “Both Paine’s friends and his enemies, patriots and loyalists alike, understood the incendiary claim that monarchy is ‘reprobated by the Almighty’ to be his most momentous contribution to the debate over independence.”[55] George Washington and others noted how the inflammatory tract kindled anti-monarchical passions: “With the view of operating on the sentiments of a religious people, scripture was pressed into his service, and the powers, and even the name of a king was rendered odious in the eyes of numerous colonists who had read and studied the history of the Jews, as recorded in the Old Testament.”[56]

Common Sense struck a chord because Paine revived polemics dormant since the English Civil War a century before, when royalist Anglican cavaliers clashed with Puritan and Presbyterian Parliament men. According to Nelson, “Paine’s republicanism had its roots in an extraordinary ideological transformation initiated by John Milton in 1651. At issue was the proper understanding of Biblical monarchy.”[57] Insofar as American Protestants were heirs of English Whigs—who saved England from the covertly Catholic Stuart kings—Paine was giving them old-time religion.

However, Paine was less a Protestant than a propagandist, and a cynical skeptic at that. Conservative Patriots saw through his feigned biblicism. John Adams remarked in a 1776 letter about Common Sense that “the Old Testament Reasoning against Monarchy would never have come from me.”[58] Unimpressed, Adams noted in his Autobiography, “One third of the book was filled with Arguments from the old Testament, to prove the Unlawfulness of Monarchy. . . His Arguments from the old Testament, were ridiculous, but whether they proceeded from honest Ignorance, or foolish Superstition on the one hand, or from willful Sophistry and knavish Hypocrisy on the other I know not.”[59] In a conversation with Paine years later, Adams charged that his reasoning from the Old Testament was ridiculous and insincere. “At this he laughed,” Adams recalled, “and said he had taken his Ideas in that part from Milton: and then expressed a Contempt of the Old Testament and indeed the Bible at large, which surprised me.”[60]

Loyalist Christians, on the other hand, took Paine’s exegesis at face value to refute it. The Anglican provost of the College of Philadelphia recognized that Common Sense needed a biblical rebuttal in “a country in which (God be thanked) the Scriptures are read, and regarded with that reverence which is due to a revelation from Heaven.”[61] Loyalists countered that Paine’s proof texts were biblical warnings against despotism, not kingship as such.[62] Another Anglican Loyalist minister attacked Paine’s reading of Judges 8:23 and 1 Samuel 8: “That simply desiring a King, could not be a crime, is undeniably evident; because the Almighty had long before expressly permitted it, had directed the mode of choosing a King, and prescribed the line of conduct the King should observe, when chosen. This is done in Deuteronomy 27:14-20.”[63] Whatever the case, the permanent effect of Common Sense was to detach American affections from the idolatrous trappings of monarchy.

Paine helped colonists disregard the title of “king,” but he did not erase monarchy in America; in the office of president, the states opted for a non-idolatrous form of it. Americans would have a monarchical executive with the power of kingly rule, but not the royal pomp, ceremony, and creed of kingly reign. If idolatry is monarchy’s problem, perhaps all that is required to tame its pretensions is to strip the office to republican simplicity, remove lifetime rule and hereditary succession, and call the occupant “Mr. President.”

In 1814, Adams reflected on a conversation with the Prince of Orange in 1788. The royal told Adams he was pleased to read the United States Constitution and had observed, “Sir, you have given yourselves a king under the title of president.” Adams admitted, “It is true, and I rejoice in it, that our presidents, limited as they are, have more power, that is more executive power, than the stadtholders, the doges, the podestàs, the avoyers, or the archons, or the kings of Lacedaemon or of Poland.”[64]

When the Framers of the Constitution drafted Article II, they patterned executive powers on a royalist theory of the king’s prerogative under the English constitution. The principles of the Patriot campaign to check Parliament “demanded in 1787 the creation of a strong, independent chief magistrate who would represent the people as a whole and tame the tyrannical proclivities and partialities of the assembly.”[65]

Now, the president has all powers Patriots demanded the king exercise on their behalf against Parliament, including a legislative veto and the nomination and removal of appointments. The presidency resembles a popular monarchy, and the president wields status over the government no less than royal courts did in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[66] Like the English Tory idea of a popular “Patriot King,” who could espouse loyalty to the people over a parliamentary faction, the president too can form an emotional bond with the public over Congress, independent of party. Hence, America has the constitutional—albeit elected—monarch Patriots wished King George had been.

In a great irony and contrast with the United Kingdom—whose royal executive is a figurehead subordinated to the prime minister of a parliamentary faction—the American republic would “evolve and perfect a recognizably Royalist constitution, investing its chief magistrate with the very same prerogative powers that Charles I had defended against the great whig heroes of the seventeenth century. On one side of the Atlantic, there would be kings without monarchy; on the other, monarchy without kings.”[67] As Adams said in a letter to Roger Sherman: “Let us now consider what our Constitution is, and see whether any other name can with propriety be given it, than that of a monarchical republic, or if you will, a limited monarchy.”[68]

Thanks to Paine popularizing an anti-monarchical reading of the Bible, America’s elected monarch is thought of, referred to, and masked merely as the republic’s chief executive.

Triumph of Post-Reformation Internationalism, Federal Union: 1787-1789

The third episode where religion, statecraft, and constitutional politics intersected was the formation of the Union, an achievement in North America of post-Reformation internationalism that became America’s hope for world order. Internationalism—or the constitutional tradition of diplomacy, in which international law and treaties integrate foreign and domestic jurisdictions—had been conceived by seminal Protestant jurists, such as Hugo Grotius and Johannes Althusius, as Europe was torn and trapped in balance-of-power politics.[69] The Founders’ position on the North American state system, and foreign policy, was indebted more to this tradition and post-Reformation federative experiments than to Machiavellian “realists” or revolutionary “idealists” like Immanuel Kant.[70]

The Articles of Confederation were supposed to balance security and sovereignty by relating the American republics in a league of friendship, but the Articles’ weakness was likely to break down into a continental balance-of-power system. Federalists sought a more perfect union to avoid North America becoming Europeanized.[71] Only by reducing the authority of the thirteen republics and integrating their sovereignties into a stronger federal system could their independence and liberty be assured. According to McDougall, “Federalists meant somehow to reconcile both order and liberty and empire and liberty in a way Rome and Great Britain had not.”[72]

America’s federal union is rightly understood as an act of international relations by governments of Protestant heritage to solve a grave geopolitical and security problem: British imperial possessions from the north, Spanish colonies from the south and southwest, and hostile or wary native tribes from the west.[73] In 1787, the thirteen American republics faced the specter of continental war, European intervention, and breakdown of their relations into rival confederacies. According to historian David Hendrickson:

Seen in this light, the American founding appears as a distinctive and most remarkable attempt to turn back the tide of war—that is, as a peace pact. It bears comparison to the great peace settlements of European and world history—Westphalia (1648), Utrecht (1713), Vienna (1815), Paris (1919), and San Francisco (1945)—save that it occurred in the anticipated prelude to rather than the bloody aftermath of a war. It may probably be considered as the most self-conscious “security community” in world history until the eighteenth century—the most innovative attempt yet to overcome the serious obstacles that states had traditionally faced in securing effective cooperation with one another. Certainly it was the first to make the attempt on a continental scale.[74]

The federal Constitution bridged the worlds of diplomacy and constitutionalism by creating a grand republic of thirteen republics, fusing characteristics of one state and a continental state system. For example, Americans have a Congress of representatives from states in the Union and not a Parliament; the former term denotes an international body in conference—such as the Congress of Vienna—while the latter is a domestic national legislature. After all, the Constitutional Convention was an international conference, conducted in secret by diplomatic designates of different states to conclude and propose a treaty creating a new system of state relations.[75]

Sensing the time pregnant with possibility, John Witherspoon told Congress:

It is but little above two hundred years since that enlarged system called balance of power, took place, and I maintain, that it is a greater step from the former disunited and hostile situation of kingdoms and states, to their present condition, than it would be from their present condition to a state of more lasting and perfect union.[76]

Witherspoon placed the founding of the Union in a line of European federative experiments meant to prevent war among diverse, including confessionally divided, polities, noting: “the union of the seven provinces of the Low Countries, has never yet been broken. . . Neither have the Cantons of Switzerland ever broken among themselves, though there are some of them protestants, and some of them papists, by public establishment.”[77] While small federative experiments had been tried, only one continental prototype had ever been conceived by Europe’s most farseeing statesmen after the Reformation, and never tried, until 1787.

The Founders’ plan for peace in North America was trying the “Grand Design” of the French King Henry IV. Henry was baptized a Catholic but raised a Protestant, barely escaped the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre, and inherited the throne in 1589. After fighting the Catholic League, Henry converted to Catholicism but issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598, guaranteeing religious liberty to Protestants. He was assassinated in 1610 by a Catholic zealot, but not before leaving a plan for balancing Catholic and Protestant interests in a federated and united Europe, a “vision which has haunted the civilized world ever since,” according to one historian.[78]

Henry IV’s “Grand Design” was a plan for post-Reformation Europe to federate Protestant and Catholic territories in a lasting continental peace.[79] He proposed to divide Europe proportionately among fifteen equal states as a hedge against balance-of-power jockeying. Cementing the union would be a constitutional settlement regarding religious, political, and commercial liberties. Legislative councils at different political scales would be composed of proportional representation and geographic distribution of the participating kingdoms, “to occupy themselves with discussing different interests, to pacify quarrels, to throw light upon and oversee the civil, political, and religious affairs of Europe, whether internal or foreign.”[80]

With the Constitution, Americans aware of this post-Reformation history recognized their federal union to be the heir of Henry IV’s dream. When James Wilson defended ratification before the Pennsylvania legislature, he declared, “Now at last is accomplished, what the great mind of Henry IV of France had in contemplation, a system of government, for large and respectable dominions, united and bound together in peace, under a superintending head, by which all their differences may be accommodated, without the destruction of the human race!”[81]

Aware their federation was a gift of peace, Americans of the Founding generation wished Europe might follow their example into a peaceful federation. Shortly after the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin wrote to a French friend, “I do not see why you might not in Europe carry the Project of good Henry the 4th into Execution, by forming a Federal Union and One Grand Republic of all its different States and Kingdoms, by means of a like convention, for we had many different Interests to reconcile.”[82]

Americans were internationalists about their state system because they moved beyond Europe’s balance of power. Indeed, it was this internationalism that drove Americans to keep attachments to Europe at arm’s length.[83] The Constitution established a model world order in North America, where member states relinquished parochial sovereignty and shared liberty, power, and security.[84] The Union was a great continental connection—promising a zone of peace, free trade, and democracy among the confederated states—where the Constitution projected the balance of power into the federal government itself.[85] This connection would keep the peace, and “this more perfect union made the United States the antithesis of the fractious European system.”[86]

Political insulation was necessary because entanglement with Europe’s state system could unravel the United States of America. European powers looked for economic and partisan cracks to play American interests off each other, replicating the Old World’s balance-of-power intrigues. Union and independence were thus mutually reinforcing imperatives, implicating “virtually all the leading principles of American diplomacy in the coming century . . . neutrality in Europe’s wars; freedom of commerce; territorial expansion; fidelity to the law of nations; an American system capable of bidding defiance to the potentates of Europe; and a belief in the radiating power of the American example[.]”[87] Union and independence supported America’s foreign and domestic tranquility.

The Constitution reckoned with the geopolitical legacy of Europe splintered confessionally by the Reformation. The founding of the United States of America—a continental state system in between interstate anarchy and imperial super-state—was an internationalist achievement in the tradition of peace pacts, concert of nations, or grand alliances that seek peace beyond balance-of-power politics.[88] America’s genius was to achieve, first and in North America, the vision of a post-Reformation Europe united and at peace.

Thoughts on America’s Moralism, Republicanism, and Internationalism

Based on this historical survey, I pose three questions and three lessons for foreign policy hands to consider about the nature of our government, focusing in turn on each prong of America’s trident of foreign policy principles.

- Is foreign policy missionary work or not?

- Is America a constitutional monarchy disguised as a republic?

- Is the business of America, America itself?

First lesson to consider—America was a moral cause from the beginning. But its moralism is an object of political struggle over what foreign policy should do. A moralism that does not recognize the historical meaning of “under God” conflates America’s revolution with secular ideologies of later revolutions. President George H. W. Bush captured the older meaning in his final State of the Union address in 1992, when he declared, “by the grace of God, America won the Cold War.”[89]

By contrast, the liberal establishment advances its own moralism with missionary zeal, tying U.S. favor to the export of its values: a progressive vision of democracy, human rights, and causes that mushroomed out of America’s own sexual revolution—pet causes alien to half of Americans, and much of the world.

Yet, a hectoring America drives fence-sitting and transactional governments into the arms of amoral adversaries. Jeanne Kirkpatrick, President Ronald Reagan’s Ambassador to the United Nations, argued after the Cold War that the United States must become “a normal country in a normal time,” concerned with promoting domestic harmony over pretensions to liberal hegemony—because, as she put it, “there is no mystical American ‘mission’ or purposes to be ‘found’ independently of the U.S. Constitution and government.”[90]

The second lesson to consider—republicanism defines Americans’ official view of our chief executive, but if the Framers modeled the presidency off a royalist theory of the English constitution, the president’s role and powers embody the Patriots’ vision of the British empire. Each president has an invitation to run foreign policy as a unifying figure over factions and sections, like the old Tory idea of a Patriot King. The great presidents—Washington, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Reagan—or presidents in their greatest moments—George W. Bush—all look like patriot kings. Bush after 9/11 was explicitly likened to the English King Henry V even by liberal commentators on MSNBC, such as Chris Matthews, who said that in Bush “the country discovered it had a young leader rising to the occasion, an easy-going Prince Hal transformed by instinct and circumstance into a warrior King Henry.”[91]

The White House is a realm of Shakespearean politics, where formal and informal advisors jockey for the president’s ear, and the National Security Council is the king’s court for foreign policy. Correspondingly, a president’s cabinet secretaries are the barons and dukes in control of the fiefdoms of federal departments and agencies. A president can choose to consolidate control into his court and run foreign policy out of the White House, or to run a “cabinet government” of empowered barons and dukes managing the kingdom in his name. A president confident in his appointees, or uninterested in foreign policy, will empower the baronies; a president sure of his judgment, or distrustful of his appointees, will hold to his own councils in the White House.

A third lesson to consider—internationalism, the federative principle as a model world order, is a stronger form of peaceful international relations than balance-of-power politics. However, internationalism is limited to a trans-Atlantic community of states anchored in North America and Europe, specifically in the United States of America, the European Union, and to a lesser degree the British Commonwealth. Beyond them is a world of interstate anarchy, imperial super-states, and power politics. The Constitution’s purpose is to politically unite confessionally divided people, which is good news for twenty-first century Americans. Yet the country’s unity is best served when leaders do not fall in love with foreign causes or tolerate unwise military adventures—bad news for Americans given our twenty-first century track record. Bad foreign policy disrupts domestic tranquility and invites foreign intrigue and lobbying to the loss of our freedom of action. Our federal union is a peace pact that can break down. It broke once.

Experts in Washington, DC live to do foreign policy, but Americans need foreign policy only so we might live in peace. Protecting the American experiment at home requires the shrewd application of our power to foreign lands, but the fundamental question of foreign policy is, “What is our business in that place, and how is America’s peace disturbed by a rival getting its way there?” We must define the boundaries of our peace: what are we content with, and what will we let go of and live with? Without such boundaries, foreign commitments become entangling because we make the business of others into our business and fall into quarrels that do not implicate the interests of Americans. Our peace can thus be needlessly disturbed as we become the busybodies of conflict, destroying our prestige, self-possession, and reputation for seriousness.

The Riddle of American Greatness: Statecraft “Under God”

Do the snapshots of religion and statecraft analyzed in this chapter matter 250 years later? However you answer, you will commit political theology. Here is my answer: yes, they do matter, because even today we carry the relics of a religious republic. Religion “is a missing link, a vital but unrecognized, even undiscovered, part of the story” of American statecraft.[92] And belief in the power of those relics answers the riddle of American identity, the question vexing our politics for the last ten years: what makes America great?

After America’s stunning victory in the Cold War, President Richard Nixon, in a final act of reflection, offered an answer to that question in his last book, published shortly before his death:

America is great because it acknowledges a power greater than itself. . . Man does not live by bread alone. Those in the United States whose desire to create a society as strong as Lenin’s was should study this Cold War lesson closely. Communism was defeated by an alliance spearheaded by ‘one nation under God.’ . . . Democracy and capitalism are just techniques unless they are employed by those who seek a higher purpose for themselves and their society.[93]

America is great because she recognizes a power greater than herself. This formulation of “one nation under God” answers the riddle of American identity by properly relating liberty and law. America is a commonwealth of republics united in an affirmation of a moral world, as constituted by law. Americans see every political authority as under a greater authority, expressed as a higher law for man, a spiritual reality beyond, but threatened by, things of raw material power.

As Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, “There are two laws discrete, not reconciled—Law for man, and law for thing. The last builds town and fleet, but it runs wild, and doth the man unking.”[94] What keeps America from becoming an imperial super-state—and from “unkinging” man’s humanity—is that it justifies political authority not by the ruling ideology of a party backed by brute force (as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics did and the People’s Republic of China does) but with appeals to standards of justice, morality, reason, and purpose open to the common man within a culture of persuasion honoring the dignity of the human being.

For its part, America’s cause is upholding that humane vision. As Kirk put it, “The American cause is not to stamp out of existence all rivals, but simply to keep alive the principles and institutions which have made the American nation great.”[95] America has been truly great when we have acted according to this cause. When we have not, America has been indistinguishable from any other regime in history. America cannot conquer and be consistent with “one nation under God.” It can only invite others to join its federation or encourage the formation of similarly principled political regimes. If America ever forgets or rejects that it is “under God,” it will become indistinguishable from an imperial super-state abroad, and slouch toward interstate anarchy at home—a house divided.

The demographic rise of the “nones,” or irreligious Americans, may shift the moral tone of U.S. foreign policy, but the greater danger lies in forgetting. Without a public that recognizes and respects the ideals embedded in our republic’s religious foundations, the nation risks careening toward secularized crusades—divorced from the historical wisdom and tempered principles of Hebraic or Christian Republicanism—or drifting into amoral power politics. It is in this quiet forgetting, rather than loud conflict, that America’s greatness may be most profoundly endangered. It is in remembering—and for the rising generation, in discovering—these things that we must place our hope, under God.

Nathan D. Hitchen holds an MA from the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, a BA from Rutgers University, and a Certificate in Nonviolent Conflict from the Institute of World Politics. He is an alumnus of the Alexander Hamilton Society’s Security and Strategy Seminars on U.S. defense policy, China, and Russia.

Image: Spectatum admissi, risum teneatis, amici? (BM 1868,0808.4560).jpg, 1776, from © The Trustees of the British Museum, released as CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spectatum_admissi,risum_teneatis,_amici%3F%28BM_1868,0808.4560%29.jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Barry Alan Shain, ed., The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context: American State Papers, Petitions, Proclamations, & Letters of the Delegates to the First National Congresses (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc., 2014), 235-236.

[2] Shain, The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context, 265-266.

[3] Andrew Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith: Religion in American War and Diplomacy (New York: Anchor Books, 2012), 71-72.

[4] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, quoted inPreston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 14.

[5]Oliver O’Donovan, The Desire of the Nations: Rediscovering the roots of political theology (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 49.

[6] Russell Kirk, The American Cause (Delaware: ISI Books, 2002), 67-69.

[7]Walter A McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy: How America’s Civil Religion Betrayed the National Interest (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 40.

[8] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 94-95.

[9] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 91-92.

[10] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 14.

[11] Shain, The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context, 5.

[12] Shain, The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context, 8.

[13] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 6.

[14] Walter A McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History, 1585-1828 (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 209.

[15] Edmund Burke, Edmund Burke’s speech on conciliation with America. Edited by Denney, Joseph Villiers Chicago, Scott, Foresman and company, 1898. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/98000700/.

[16] Walter Russell Mead, God and Gold: Britain, America, and the Making of the Modern World (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 24.

[17] Mead, God and Gold, 29-31.

[18] Mead, God and Gold, 35.

[19] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 74.

[20] “From John Adams to John Jay, 10 August 1785,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-17-02-0175. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 17, April–November 1785, ed. Gregg L. Lint, C. James Taylor, Sara Georgini, Hobson Woodward, Sara B. Sikes, Amanda A. Mathews, and Sara Martin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014, pp. 321–323.]

[21] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 96.

[22] McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner, 209.

[23] McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy, 40.

[24] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 90-91.

[25] McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy, 27.

[26] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 13.

[27] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 11.

[28] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 68.

[29] Peter Onuf and Nicholas Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World: The Law of Nations in an Age of Revolutions, 1776-1814 (Madison: Madison House Publishers, Inc., 1993), 100-101.

[30] McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy, 27.

[31] Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, Fiftieth Anniversary Edition (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017), 204-205.

[32] Gregg L Frazer, God Against the Revolution: The Loyalist Clergy’s Case Against the American Revolution (Lawrence: The University Press of Kansas, 2018), 189-193.

[33] McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner, 222.

[34] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 23.

[35] McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner, 211.

[36] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 21.

[37] Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 98.

[38] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 24.

[39] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 32.

[40] The Mitred Minuet. United States England, 1774. [May 1] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004672698/.

[41] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 189.

[42] Shain, The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context, 241.

[43] Richard B Vernier, ed., The Revolutionary Writings of Alexander Hamilton (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Inc., 2008), 29.

[44] Vernier, The Revolutionary Writings of Alexander Hamilton, 151.

[45] Vernier, The Revolutionary Writings of Alexander Hamilton, 150.

[46] Vernier, The Revolutionary Writings of Alexander Hamilton, 143.

[47] McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner, 236.

[48] Thomas Paine, Common Sense: Addressed to the Inhabitants of America (Middletown: Coventry House Publishing, 2016), 21.

[49] Eric Nelson, The Royalist Revolution: Monarchy and the American Founding (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014), 2.

[50] Shain, The Declaration of Independence in Historical Context, 194-199.

[51] Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution, 124.

[52] Paine, Common Sense, 32.

[53] Paine, Common Sense, 44.

[54] Paine, Common Sense, 12.

[55] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 112.

[56] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 111.

[57] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 117.

[58] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 113.

[59] L.H. Butterfield, ed., Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, 3 vols. (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1961), 3:330-331.

[60] Butterfield, Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, 3:333.

[61] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 133.

[62] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 62-63.

[63] Frazer, God Against the Revolution, 62.

[64] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 144.

[65] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 186.

[66] Onuf and Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World, 88.

[67] Nelson, The Royalist Revolution, 232.

[68] “From John Adams to Roger Sherman, 18 July 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-20-02-0055. [Original source: The Adams Papers, Papers of John Adams, vol. 20, June 1789–February 1791, ed. Sara Georgini, Sara Martin, R. M. Barlow, Gwen Fries, Amanda M. Norton, Neal E. Millikan, and Hobson Woodward. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020, pp. 81–83.]

[69] Onuf and Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World, 108.

[70] David C Hendrickson, Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2003), xii.

[71] Onuf and Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World, 129.

[72] McDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner, 312.

[73] McDougall, The Tragedy of U.S. Foreign Policy, 34.

[74] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, x-xi.

[75] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 258-259.

[76] Onuf and Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World, 101.

[77] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 143.

[78] Joseph E. Keller, “Henry IV and World Peace,” Minnesota Law Review vol. 31 (1947): 396, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1696.

[79] Keller, “Henry IV and World Peace,” 390-396, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1696.

[80] Keller, “Henry IV and World Peace,” 393, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/1696.

[81] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 23.

[82] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 23.

[83] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 176.

[84] Onuf and Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World, 135-136.

[85] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 258-259.

[86] Onuf and Onuf, Federal Union, Modern World, 148.

[87] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 201.

[88] Hendrickson, Peace Pact, 145-146.

[89] George H. W. Bush, “State of the Union Address,” January 28, 1992, Miller Center, University of Virginia, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-28-1992-state-union-address.

[90] William Smith, “Jeane J. Kirkpatrick: 30 Years Unheeded,” The National Interest, 13 June 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/jeane-j-kirkpatrick-30-years-unheeded-162667.

[91] Ben Brantley, “George W/Henry V,” Big Think, 7 April 2011, https://bigthink.com/culture-religion/george-whenry-v/.

[92] Preston, Sword of the Spirit, Shield of Faith, 7.

[93] Richard Nixon, Beyond Peace (New York: Random House, Inc., 1994), 19-21.

[94] “Ode, Inscribed to William H. Channing” from: Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Early Poems of Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York, Boston, Thomas Y. Crowell & Company: 1899. Introduction by Nathan Haskell Dole. https://emersoncentral.com/texts/poems/ode-to-william-h-channing/.

[95] Kirk, The American Cause, 12.