Security and Strategy Journal

How the United States Can Fight and Win in the Cognitive Domain

Share On:

In May 2024, U.S. troops began withdrawing from Niger after the country ended a military agreement several months earlier that allowed the U.S. Department of Defense to operate from the country.1 A Nigerien military spokesman provided a murky explanation for his country’s decision, characterizing the previous agreement with the United States as “profoundly unfair” and claiming that it did “not meet the aspirations and interests of the Nigerien people.”2

General Michael Langley, head of United States Africa Command, placed the blame for the withdrawal of U.S. troops squarely on Russia in his March 2024 congressional testimony.3 Gen. Langley claimed that the “Russian Federation’s narrative drowned out the U.S. government’s in the past years… across the Sahel,” where Russia conducted aggressive and savvy “misinformation [and] disinformation campaigns.”4 It is likely not a coincidence that, weeks after Niger ended its military agreement with the United States, Russian troops began operating out of the same military base U.S. troops had used.5

Russian adversarial influence operations in Niger contributed to tangible consequences for the United States—not merely a nebulous decrease in pro-U.S. sentiment, but the loss of a military base that cost the U.S. taxpayer over $280 million.6 On top of this financial loss, the U.S. withdrawal from Niger allows Russia to easily deploy drones in Niger to threaten the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) southern flank and Iran to access Niger’s uranium reserves.7 These threats are not merely hypothetical. Iran purchased 300 tons of concentrated uranium from Niger after the expulsion of U.S. troops.8 America has not merely lost a popularity contest with Russia in Niger, losing the cognitive war to Russia has increased America’s strategic threats.

The incident in Niger illustrates what it means for the United States to lose a certain type of fight against its adversaries; however, it is difficult to assign a precise name to this battle. Various terms could apply, such as information warfare or cognitive warfare. Regardless of what one chooses to call this competition, one fact remains clear: the United States’ adversaries routinely wield information to advance their interests and undermine U.S. interests abroad.

What does it look like for the United States to fight in this domain—hereafter referred to as the cognitive domain—and win? First, the United States must constantly monitor for adversarial activity in the cognitive domain and aggressively counter this activity as soon as it emerges. Without effectively responding to adversarial efforts, the United States cannot even put up a fight in the cognitive domain. Secondly, the United States must shape the information environment in regions of strategic importance in advance of adversarial activity so that these regions remain favorable to the interests of the United States and unfavorable to adversarial interests. These proactive efforts will not only allow the United States to more effectively fight its adversaries in the cognitive domain, but will also help the United States win current and future cognitive conflicts by advancing its long-term objectives in strategically important regions.

Defining Competition in the Cognitive Domain

The terms information warfare and cognitive warfare both describe the types of competition this paper seeks to address. The term cognitive warfare helpfully focuses on the cognitive, human-centric dimension of information, and clearly distinguishes it from forms of information warfare such as cyber-attacks on computers and networks.9 This paper primarily concerns itself with activity that wields information to shape human beliefs and behaviors, rather than activity that wields information to shape the behavior of computers and other machines. This paper also broadly concerns itself with activities that fall beyond the scope of conventional warfare, and even beyond the scope of irregular warfare, as it does not exclusively seek to address military activity.10 Broadly speaking, this paper seeks to address competition in the cognitive domain between the United States and its adversaries, spanning both military and non-military forms of competition.

How to Lose in the Cognitive Domain (Part 1): Russia Undermining U.S. Interests in Niger

Russia did not undermine U.S. interests in Niger overnight, but spent several years targeting Niger to shape its information environment in line with Russian interests. Russian influence in Niger aligns with three discrete timeframes: before the 2023 Nigerien coup, immediately after the coup, and following the expulsion of U.S. forces in May 2024. Moving through each period chronologically demonstrates how Russia successfully increased its influence over time leveraging multiple means. Russia primarily launched covert online influence operations before the coup, then additionally began funding civil society after the coup, and, after the expulsion of American troops, engaged in full-scale security and economic cooperation.11

At least as far back as 2018, Russia targeted African countries through covert influence operations, as demonstrated by a report from the Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO) that exposed Russia-linked networks on Facebook.12 Part of the networks’ activities attempted to cast the United States, France, and the United Nations (UN) in a negative light. For example, one post criticized the president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for pursuing closer ties with the United States.13 Part of the networks’ activities also attempted to depict Russia in a favorable light, for example, by creating a post commemorating Miss Russia’s visit to the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2013 and by rejecting claims that Russian mercenaries tortured victims in CAR.14

While the networks exposed by SIO targeted eight African countries, SIO did not identify Russian activity targeting Niger.15 The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), in a report that has since been removed from the internet, found evidence of Russian influence operations targeting Niger starting as far back as 2020.16 One of the earliest documented, specific cases of pro-Russian activity targeting Niger involves a Facebook page that joined a broader network of Pro-Russian pages in November 2021.17 This page, which was exposed by the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab), was titled “Reveil des Peuples du Sahel” (Awakening of the People of the Sahel).18 The page promoted the “liberation” of people in the Sahel and reportedly placed particular focus on Niger and Burkina Faso.19 On the day of its creation in November 2021, the page called for the people of Sahel to throw a revolution and, in February 2022, the same page called for the immediate withdrawal of troops from all foreign military bases in Niger.20

The Africa Center for Strategic Studies, which has sought to comprehensively document influence operations targeting Africa, identified the pro-Russian activity exposed by DRFLab as one of only two influence operations targeting Niger up until 2022.21 A similar study released by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies found that the number of influence operation campaigns involving Russia-linked actors had increased to five total operations between 2022 and 2024.22 This period notably spans the 2023 Nigerien coup, after which Russian influence operations targeting Niger became increasingly aggressive.

Research from Logically, a British company that develops technology to monitor information environments, found that Niger-related content across 45 Russian Telegram channels—either affiliated with the Russian State or the Wagner Paramilitary Group—increased by 6,645 percent in the month after Niger’s July 2023 coup.23 A notable post from this period, shared by a Russia-linked Telegram channel, portrays Moscow and Beijing as leading a broader anti-colonial movement across Niger and the Sahel region, and claims that many African countries hope to join BRICS, a political bloc that the Kremlin has positioned as an alternative to the U.S.-led world order.24

After the 2023 Nigerien coup, Russia not only increased its covert social media activity but also introduced new tactics, such as covertly funding civil society organizations to increase pro-Russian sentiment. For example, the Russian Foreign Ministry created a civil society organization called PARADE Niger that handed out Russian flags at protests in Niger’s capital and other Nigerien cities in addition to amplifying content from pro-Russian propaganda outlets such as Afrique Média on social media.25 The president of PARADE Niger even admitted to The New York Times that he worked with the Russian government to “develop the expansion of Russian ideology in Africa.”26

The activities exposed by SIO, DFRLab, Logically, and The New York Times demonstrate that Russia not only took long-term actions to shape the information environment in Niger as far back as 2020, it also capitalized upon a critical phase of political upheaval in Niger in 2023 to further draw Niger toward Russian interests and away from U.S. interests. After the expulsion of U.S. troops, Russia began cementing its influence in the region through multiple means that go beyond online and offline influence operations. In April 2024, Russia sent military personnel and anti-aircraft systems to Niger to increase defense cooperation.27 In October 2024, a Russian cultural organization known as Rossotrudnichestvo—which acts on behalf of the Russian foreign ministry and intelligence agencies—opened up a Russian house that teaches Russian language courses, screens films from Russian state media, provides scholarships to study in Russian universities, and engages in a range of other activities to increase Russian influence in Niger.28

Though Russia clearly launched online and offline influence operations seeking to foment anti-Western sentiment in advance of the 2023 Nigerien coup and during the immediate aftermath, assessing the impact of adversarial influence operations remains a notoriously difficult endeavor.29 One might argue, for example, that Russian online influence operations could not have contributed to Niger’s turn to Russia, as only four percent of Nigeriens were online when Russian influence operations in Africa began in 2018, and only 24 percent were online as of 2024.30 For context, over 90 percent of the population in high-income countries is typically online.31 However, anecdotal evidence suggests that Russian online and offline influence operations did have an impact in Niger, though it may now be impossible to precisely measure the scale and severity of this impact. The New York Times in October 2023 interviewed Nigeriens who considered the Russian flag to be a trendy fashion statement at the time and others who explicitly stated their views on Russia shifted after being exposed to pro-Russian content on social media.32

How to Lose in the Cognitive Domain (Part 2): U.S. Response to Russian Activity in Niger

The U.S. government did, in fact, respond to Russian influence operations targeting Niger. As mentioned earlier, USAID commissioned a study titled “Disinformation in Niger,” published in January 2021, which “found evidence of Russia pushing self-serving narratives to delegitimize U.S. presence in Niger” between January and December of 2020.33 In 2021, the Department of State announced grants to fund a U.S. Mission to Niger to support “journalism, media literacy, and countering disinformation.”34 In 2022, the U.S. Embassy in Niger sponsored a trip for professors from the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism to “show journalists how to spot disinformation and tell compelling stories.”35 While the University of Missouri does not mention Russian activity targeting Niger in its press release referring to the trip, it is plausible that countering Russian activity was a goal of this broader counter-disinformation effort.36 The websites of Indiana University and the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill both also refer to an apparently ongoing Department of State project to develop a “Niger Online Disinformation Tracker” that offers “real-time insights into the sources and spread of misleading content.”37

U.S. efforts to counter Russian activity that seeks to undermine U.S. interests in Niger include exposing Russian adversarial activity and undermining Russia’s reputation in the region. The U.S. government has almost no public efforts to undermine Russia’s reputation in Niger, other than a lone blog from 2022 on the website of the U.S. Embassy in Niger that calls out Russia for spreading disinformation about Ukraine.38 As many U.S. offensive operations in the cognitive domain are highly sensitive, there may have been more U.S. activity against Russia in Niger that is not public.

While the full extent of U.S. efforts to counter Russian influence operations targeting Niger may not be publicly available, its various efforts clearly did not effectively blunt the impact of Russia’s adversarial activity. Empirically measuring the effect of influence operations remains a difficult endeavor, and one could argue that Russian adversarial influence targeting Niger merely correlated with the withdrawal of U.S. troops from the region, rather than causing it.39 However, considering the end result in which U.S. troops withdrew from Niger, it is likely that Russia’s years-long efforts to undermine U.S. interests in Niger through cognitive domain operations actually contributed to the U.S. failure in the region. Moreover, the United States’ response appears to have done little to stop it.

How to Fight in the Cognitive Domain: The United States Should Have More Aggressively Countered Russian Adversarial Activity in Niger

If the United States had taken a different approach to countering Russian adversarial activity in Niger it likely would have better preserved its own interests while undermining Russia’s interests. Gen. Langley of U.S. Africa Command, in his congressional testimony, requested access to “more capabilities in the Department of State from their Global Engagement Center” as well as more capabilities from “information operations in the military” in order to counter Russian activities in Niger.40 While the Global Engagement Center lost legislative authority in 2024, Gen. Langley’s remarks raise the question as to which specific capabilities the U.S. government needs to counter Russian adversarial activity in Niger, and which U.S. government organizations can provide these capabilities.41

To implement a more effective response to counter Russian adversarial activity in Niger, the U.S. government could have benefited from continuous monitoring, detection, and response. Continuously monitoring the information environment in Niger would have involved observing online and offline media that is consumed by Nigeriens through real-time data collection, analysis, and risk assessments to gain ongoing situational awareness. This continuous monitoring would have, in turn, enabled detection of adversarial activity seeking to undermine U.S. interests in Niger, allowing the United States to then respond to this activity in an efficient and effective fashion.

Continuous monitoring and detection are essentially analytic functions. They do not require putting out information, but rather, collecting and interpreting information. U.S. government agencies that could have helped with these efforts in Niger include various agencies within the intelligence community—such as the Defense Intelligence Agency and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s Foreign Malign Influence Center—as well as military intelligence units within the U.S. Department of Defense, including United States Africa Command’s directorate of intelligence.42 The most suitable organization to engage in monitoring this activity, however, would be the intelligence community’s Open Source Enterprise, which is tasked with monitoring foreign media activity spanning print, broadcast, and online media.43

Organizations involved in detection and analysis could have coordinated their activities by taking an interagency approach across the U.S. Department of Defense and non-U.S. Department of Defense elements. To carry out continuous monitoring, this interagency effort could have employed specialized technology such as social listening tools that continuously collect and analyze massive amounts of data from online sources to surface significant trends across traditional and social media.44 These organizations then could have applied a combination of open-source intelligence, social media intelligence, and cyber-threat intelligence to detect when various trends in Niger’s information environment resulted from Russian adversarial activity.45

The United States should also have projected information that limited the effectiveness of adversarial attempts to undermine U.S. interests in the cognitive domain. These communications could serve a number of aims, including: exposing Russian influence operations to Nigeriens so that Nigeriens understand that Russia seeks to manipulate them; diplomatic engagement to assuage concerns with the Nigerien government about U.S. troops in Niger; and media campaigns that seek to cast the United States and its presence in Niger in a positive light, while casting Russia and its presence in Niger in a negative light.

U.S. government organizations that have historically been involved in publicly exposing foreign influence operations targeting foreign countries include the U.S. Department of State’s now-defunct Global Engagement Center and USAID. For example, in February 2024, only a month before Niger’s troops ordered the withdrawal of U.S. troops, the Global Engagement Center exposed a Russian influence operation targeting Africa, though this campaign does not appear to have specifically targeted Niger.46 USAID also published a report on Russian influence operations targeting Niger.47 Today, the Global Engagement Center no longer exists and the current administration seeks to end USAID, which raises the question as to which U.S. government agencies can expose foreign influence operations targeting foreign audiences in the future.48 The U.S. Department of State previously trained Nigerien journalists to expose Russian disinformation and this provided an indirect means of exposing Russian adversarial activity, but a U.S. government agency dedicated to exposing foreign influence operations targeting foreign countries could provide critical capabilities in the cognitive domain.49

The Department of State could have more proactively engaged with the new Nigerien government after they seized power in July 2023 to assuage any concerns they may have had about American troops in Niger. Although the Department of Defense released a statement claiming that a delegation of Department of Defense and Department of State officials met with the Nigerien government to warn against Niger moving closer to Russia and Iran and to discuss the status of U.S. troops in Niger, this delegation did not effectively convince the Nigerien government to maintain a U.S. troop presence in Niger.50 Considering that seven months transpired between the coup in Niger and the delegation’s visit, the Department of State—recognizing that Niger had undergone significant changes in leadership and that Russia had been targeting Niger with influence operations for years—should have more proactively sent a delegation to Niger. Proactive, sustained diplomatic engagement could have more successfully influenced the Nigerien government to keep U.S. troops in Niger.

The United States could also have responded to Russian activity undermining U.S. interests in Niger by disseminating information favorable to the United States and unfavorable to Russia and its military. U.S. government organizations and personnel who could have carried out these campaigns include Department of State public diplomacy officers and military psychological operations units. The U.S. government’s state media outlets, diplomats, and soldiers could have coordinated their efforts to cast the United States in favorable light, for example, by highlighting humanitarian initiatives in Niger. They could have also aggressively maligned Russia’s reputation by framing Russia as a repressive regime seeking to exploit Africa for its natural resources. The U.S. government should also be able to measure the effectiveness of its own activities in the cognitive domain. Assessing the impact of information remains difficult and is actively debated in military circles, but without the effective assessments, America will essentially be shooting in the dark.51

Countering Russian activity that undermines U.S. interests in Niger involves a complex effort in which various military elements and non-military organizations must closely coordinate their activities to effectively implement continuous monitoring, detection, and response. The U.S. government would have benefited from having an organization dedicated to coordinating various cognitive domain activities among the intelligence community, the Department of Defense, the Department of State, and USAID. This dedicated organization could have lent coherence and cohesion to the government’s competition in the cognitive domain, and could have ensured that U.S. efforts were proactive and aggressive enough to successfully undermine Russia’s adversarial activity in Niger. This same organization would also ideally oversee efforts to counter cognitive domain activity against the United States across the globe, regardless of the actor or the region that the actor targets.

How to Win in the Cognitive Domain: Proactively Identify and Begin Engaging with Regions of Strategic Importance

While the U.S. government should assess its activities in Niger between 2020 and 2024 to understand why it lost the competition with Russia in the cognitive domain, one lesson is abundantly clear: America has already missed the early boat and must act now to start winning the war for hearts and minds. Moreover, in a battlefield as complex and crucial as the cognitive domain, it is never too early to start fighting.

In 2019, Dr. Joseph Siegle, Director of Research at the Africa Center, provided a picture of what a more aggressive, proactive U.S. response to Russian activities in Africa could have looked like in the cognitive domain.52 Dr. Siegle encouraged the United States to convey “the Russian link to instability and exclusionary regimes… to African citizens – through multiple channels, including trusted media, civil society, and social media networks.”53 Dr. Siegle argued this “awareness raising” could have created a “reputational cost for Russia” that would “spill across borders and affect Russia’s ability to negotiate trade, investment, and security cooperation deals elsewhere on the continent.”54 If the United States had undertaken Dr. Siegle’s recommendations in 2019, it is plausible that U.S. troops may still be in Niger today. Here, it is important to remember that having U.S. troops in Niger served vital U.S. interests such as helping to combat Islamic terrorist groups, including Al Qaeda, in the region.55 Moreover, considering that armed Islamist groups continue to commit violent acts in Niger and other countries in the central Sahel, U.S. counter-terrorism operations in Niger could have also benefited the people of Niger.56

As soon as the U.S. government signed its military agreement with Niger in 2013, and even before it was signed—that is, at the very moment when it first deemed Niger to be a region of strategic importance to the United States—it should have begun proactively and aggressively acting in the cognitive domain.57 This does not mean that the United States should have only promoted a positive attitude toward America in Niger. It also means that the United States should have closely monitored for the activity of U.S. adversaries that sought to undermine its interests in Niger, and that the U.S. government should have aggressively countered those activities as soon as they emerged.

Learning a lesson from its failure in Niger, the United States should immediately begin identifying regions of strategic importance and begin assessing whether U.S. adversaries are currently competing with the United States in the cognitive domain in these regions. Are there countries in the Indo-Pacific where China seeks to discredit America to undermine their military partnerships with the United States? Are there countries of economic importance to the United States where China seeks to discredit America to establish itself as the preferred trade partner? Are there regions critical to U.S. counterterrorism operations in the Middle East where Iran seeks to co-opt emerging militant groups to expand its Axis of Resistance? Are there countries in Eastern Europe where Russia seeks to foment anti-American sentiment to prevent cooperation with the United States and its partners in Europe?

Once these regions of strategic importance are identified, the United States should begin cataloging and assessing its various forms of competition in the cognitive domain in these regions. The U.S. government should consider all of its activities in these regions that could potentially be construed as contributing to this competition including, but not limited to: public diplomacy carried out by the Department of State, operations in the information environment (OIE) conducted by the Department of Defense, and development programs that previously would have been sponsored by USAID. Once the United States has assessed its various activities, it should consider the activities of its adversaries in these contested regions. Drawing upon past failures, the United States should assess whether it is acting aggressively enough in the cognitive domain to counter current and future aggressive actions carried out by its adversaries.

For America to win in the cognitive domain, it should also preempt future regions of strategic importance and begin fighting to win the war of hearts and minds in these regions. America should determine where the future population and economic hubs will be located and begin acting in these regions now. The UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs predicted in 2017 that by 2050 half of global population growth will be concentrated in nine countries. Aside from the United States itself, these countries include India, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Pakistan, Ethiopia, the United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda and Indonesia.58 PWC also projects that China, India, and Indonesia will be the world’s largest economies by 2050.59

The United States should turn toward these future economic and population hubs and begin conducting cognitive domain operations in these regions now. This can begin by assessing what the current attitudes toward the United States are in these regions, what actions on behalf of regional governments and local populations would benefit the United States, and identifying whether and how adversaries are already wielding influence as a weapon in these countries. The United States should then begin crafting a strategy specific to each region to ensure that it will achieve dominance in the cognitive domain in these regions of strategic importance by 2050.

If the United States had crafted a long-term strategy and begun competing in the cognitive domain in Niger as soon as it deemed Niger a region of strategic importance, it may have been able to effectively outcompete Russia’s activities seeking to undermine U.S. interests in Niger. The U.S. government must act now to ensure it does not make the same mistakes in present and future regions of strategic importance. The consequences of the United States losing in the cognitive domain in Niger involved the withdrawal of U.S. troops from a region that plays a critical role in U.S. counterterrorism operations, the loss of hundreds of millions in taxpayer dollars, and the ability for Russia and Iran to increasingly threaten U.S. allies through drone activity and accessing uranium reserves.60 The consequences of the United States losing in the cognitive domain in present and future regions of strategic importance will likely prove even more severe. The war for hearts and minds is more than a mere popularity contest. The future of a U.S.-led world order hinges upon America’s ability to fight in the cognitive domain, and win.

Max Lesser is the Senior Analyst on Emerging Threats at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies where he focuses on foreign malign influence, cyber-enabled influence operations, and other hybrid threats. He graduated Harvard with a bachelor’s degree in English. Max is an alumnus of SSS China.

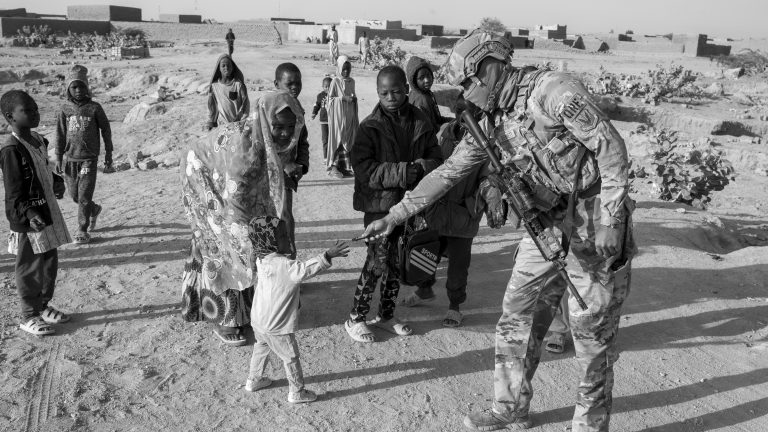

Image: Air Force Senior Airman Lorenzo Bennette hands candy to a child near Air Base 201 in Niger, Jan. 6, 2023, January 5, 2023, from Air Force Master Sargent Michael Matkin. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Air_Force_Senior_Airman_Lorenzo_Bennette_hands_candy_to_a_child_near_Air_Base_201_in_Niger,_Jan._6,_2023.jpg, used under Wikimedia Commons.

[1] United States Africa Command Public Affairs, “U.S. Withdrawal from Niger Completed,” United States Africa Command, June 7, 2024, https://www.africom.mil/pressrelease/35590/us-withdrawal-from-niger-completed; Declan Walsh, “Niger Orders American Troops Out,” New York Times, March 17, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/17/world/africa/niger-orders-american-troops-out.html.

[2] Haley Britzky, “US Military Completes Withdrawal from Niger,” CNN, September 16, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/09/16/politics/us-military-niger-withdrawal/index.html.

[3] Haley Britzky, “Senior US general warns about Russia’s growing influence in Africa,” CNN, March 7, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/03/07/politics/general-warns-russia-influence-africa/index.html; Patrick Tucker, “Russia’s Lies Helped Persuade Niger to Eject US Troops, AFRICOM Says,” Defense One, March 21, 2024, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2024/03/top-us-commander-africa-pleads-resources-counter-russian-disinformation/395145/.

[4] Britzky, “Senior US general.”

[5] Natasha Bertrand, “Niger: Russian Forces Are Operating at Same Base as US Troops,” CNN, May 3, 2024, https://www.cnn.com/2024/05/02/politics/us-russian-forces-niger-base/index.html.

[6] Matthew Petti, “America’s $280 Million Military Mission in Niger Ends in Failure,” Reason, March 19, 2024, https://reason.com/2024/03/19/americas-280-million-mission-in-niger-ends-in-failure/.

[7] Liam Karr, “Africa File Special Edition: Niger Cuts the United States for Russia and Iran,” Institute for the Study of War, March 21, 2024, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/africa-file-special-edition-niger-cuts-united-states-russia-and-iran.

[8] Banafsheh Zand, “Iran and Niger Cement Alliance With Secret ‘Yellowcake’ Uranium Deal,” Iran International, June 1, 2024, http://www.iranintl.com/en/202405319613.

[9] Christoph Deppe and Gary S. Schaal, “Cognitive Warfare: A Conceptual Analysis of the NATO ACT Cognitive Warfare Exploratory Concept,” Frontiers in Big Data 7 (2024), https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2024.1452129; Alonso Bernal et al., “Cognitive Warfare: An Attack on Truth and Thought,” Innovation Hub (Fall 2020), https://innovationhub-act.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Cognitive-Warfare.pdf.

[10] U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Defense Primer: What Is Irregular Warfare?, by Catherine A. Theohary, IF12565 (2024), https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF12565.

[11] Manisha Aryal, “Disinformation In Niger: Trends and Recommendations,” United States Agency for International Development, January 28, 2021, accessed December 1, 2024, https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00X8TH.pdf; Adam Nossiter, “Russian Flags in West Africa: A Symbol of Resistance or Influence?” New York Times, October 1, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/01/world/africa/russian-flags-west-africa-niger.html; “Russia and Niger agree to develop military ties, Moscow says,” Reuters, January 16, 2024, http://www.reuters.com/world/russia-niger-agree-develop-military-ties-moscow-says-2024-01-16/.

[12] Shelby Grossman, Daniel Bush, and Renée DiResta, “Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations in Africa,” Stanford Internet Observatory, October 29, 2019, https://fsi.stanford.edu/publication/evidence-russia-linked-influence-operations-africa.

[13] Grossman, Bush, and DiResta, “Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations.”

[14] Grossman, Bush, and DiResta, “Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations.”

[15] Grossman, Bush, and DiResta, “Evidence of Russia-Linked Influence Operations.”

[16] Aryal, “Disinformation In Niger.”

[17]DFRLab, “Pro-Russian Facebook Assets in Mali Coordinated Support for Wagner Group, Anti-Democracy Protests,” Medium, February 16, 2022, https://medium.com/dfrlab/pro-russian-facebook-assets-in-mali-coordinated-support-for-wagner-group-anti-democracy-protests-2abaac4d87c4.

[18] DFRLab, “Pro-Russian Facebook Assets.”

[19] DFRLab, “Pro-Russian Facebook Assets.”

[20] DFRLab, “Pro-Russian Facebook Assets.”

[21]Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Mapping Disinformation in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 26, 2022, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mapping-disinformation-in-africa/.

[22] Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Mapping a Surge in Disinformation in Africa,” Africa Center, March 13, 2024, https://africacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Regional-Map-of-Disinformation-in-Africa-2024.pdf.

[23] Jason Burke, “Russia Uses Social Media Channels to Exploit Niger Coup,” The Guardian, August 27, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/27/russia-uses-social-media-channels-to-exploit-niger-coup.

[24] Burke, “Russia Uses Social Media Channels.”

[25] Nossiter, “Russian Flags in West Africa;” Microsoft Threat Analysis Center, “Russia’s Influence Networks in Sahel Activated After Coups,” Microsoft, September 1, 2023, https://blogs.microsoft.com/wp-content/uploads/prod/sites/5/2023/09/Sahel-Gabon-Coup-Playbook-PDF.pdf.

[26] Nossiter, “Russian Flags in West Africa.”

[27] Petti, “America’s $280 Million Military Mission.”

[28] “Russian House Officially Opened in Niamey,” African Initiative, October 2, 2024, http://web.archive.org/web/20250414100336/https://afrinz.ru/en/2024/10/russian-house-officially-opened-in-niamey/; Ivan U. Klyszcz, “Rossotrudnichestvo in Africa: Propaganda and Soft Power,” EUvsDisinfo, October 22, 2024, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/rossotrudnichestvo-in-africa-propaganda-and-soft-power/.

[29] Jon Bateman et al., “Measuring the Effects of Influence Operations: Key Findings and Gaps from Empirical Research,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/06/measuring-the-effects-of-influence-operations-key-findings-and-gaps-from-empirical-research?lang=en#effects/?lang=en.

[30] Simon Kemp, Digital 2018: Niger, DataReportal, February 1, 2018, http://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2018-niger; Simon Kemp, Digital 2024: Niger, DataReportal, February 2024, https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2024-niger.

[31] International Telecommunication Union, Facts and Figures 2024 — Internet Use, November 10, 2024, https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/2024/11/10/ff24-internet-use/.

[32] Nossiter, “Russian Flags in West Africa.”

[33] Aryal, “Disinformation In Niger,” https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00X8TH.pdf.

[34] FundsforNGOS, “U.S. Mission to Niger: American Corner-Journalism, Media Literacy, and Countering Disinformation,” FundsforNGOS, accessed February 22, 2025, https://www2.fundsforngos.org/latest-funds-for-ngos/u-s-mission-to-niger-american-corner-journalism-media-literacy-and-countering-disinformation/.

[35] “In Niger, Missouri School of Journalism Professors Show Journalists How to Spot Disinformation and Tell Compelling Stories,” Missouri School of Journalism, February 8, 2022, https://journalism.missouri.edu/2022/02/in-niger-missouri-school-of-journalism-professors-show-journalists-how-to-spot-disinformation-and-tell-compelling-stories/.

[36] “In Niger, Missouri School of Journalism.”

[37] Embassy Niamey Public Affairs Office, “Niger Online Disinformation Tracker (NODT),” Indiana University, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, accessed February 22, 2025, https://global.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/982/2024/09/Africa_DL-Projects.pdf.

[38] U.S. Embassy in Niger, “Remarks by Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield at a UN Security Council Meeting Called by Russia to Spread Disinformation About Ukraine,” U.S. Embassy in Niger, March 14, 2022, https://ne.usembassy.gov/remarks-by-ambassador-thomas-greenfield-at-a-un-security-council-meeting-called-by-russia-to-spread-disinformation-about-ukraine/.

[39] Bateman et al., “Measuring the Effects.”

[40] Tucker, “Russia’s Lies.”

[41] U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Termination of the State Department’s Global Engagement Center, by Matthew C. Weed, IN12475, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN12475.

[42] U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, https://www.state.gov/bureaus-offices/secretary-of-state/bureau-of-intelligence-and-research/; United States Africa Command, “U.S. Africa Command Directorate for Intelligence,” https://www.africom.mil/about-the-command/directorates-and-staff/j2—intelligence.

[43] Steven Aftergood, “Open Source Center (OSC) Becomes Open Source Enterprise (OSE),” Federation of American Scientists, October 28, 2015, https://fas.org/publication/osc-ose/; Intelligence Resource Program, “Director of National Intelligence — Open Source Center,” Federation of American Scientists, accessed April 14, 2025, https://irp.fas.org/dni/osc/index.html.

[44] Anna Grizāne, Marija Isupova, Vanessa Vorteil, Social Media Monitoring Tools: An In-Depth Look, NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence, July 2022, https://stratcomcoe.org/pdfjs/?file=/publications/download/Social-Media-Monitoring-Tools-DIGITAL-a23c5.pdf?zoom=page-fit.

[45] Flashpoint, “What Is Malign Influence and How Can OSINT Address It?” Flashpoint, December 7, 2021, https://flashpoint.io/blog/malign-influence-osint/; OSINT Industries Team, “Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT) in Modern Investigations,” OSINT Industries, accessed February 22, 2025, https://www.osint.industries/post/social-media-intelligence-socmint-in-modern-investigations; “Countering Malign Influence: Kill Chains and Frameworks,” Booz Allen Hamilton, accessed February 22, 2025, https://www.boozallen.com/insights/cyber/tech/countering-malign-influence-kill-chains-and-frameworks.html.

[46] U.S. Department of State, Global Engagement Center, The Kremlin’s Efforts to Spread Deadly Disinformation in Africa, accessed February 22, 2025, https://2021-2025.state.gov/the-kremlins-efforts-to-spread-deadly-disinformation-in-africa-2/.

[47] Aryal, “Disinformation In Niger.”

[48] Ellen Knickmeyer and Meg Kinnard, “What USAID Does, and Why Trump and Musk Want to Get Rid of It,” Associated Press, February 4, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/usaid-foreign-aid-freeze-trump-peter-marocco-8253d7dda766df89e10390c1645e78aa.

[49] “In Niger, Missouri School of Journalism.”

[50] David Vergun, “U.S. Working Diplomatically With Niger on New Path of Cooperation,” U.S. Department of Defense, March 18, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/article/3710272/us-working-diplomatically-with-niger-on-new-path-of-cooperation/.

[51] Steven D. Santa Maria, Improving Influence Operations By Defining Influence And Influence Operations, School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, February 2013, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA606282.pdf; Krystel Carrier-Sabourin, Measuring Effects and Success in Influence Operations (Contract Report), Defence R&D Canada, April 2011, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA568381.pdf; Christopher W. Weimer, Forecasting Effects of Influence Operations: A Generative Social Science Methodology (Thesis), Air Force Institute of Technology, March 2012, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA558577.pdf.

[52] Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Profile: Dr. Joseph Siegle, Director of Research,” accessed February 22, 2025, https://africacenter.org/experts/joseph-siegle/; Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Recommended US Response to Russian Activities in Africa,” Expert Publication (blog), accessed February 22, 2025, https://africacenter.org/experts/joseph-siegle/recommended-us-response-to-russian-activities-in-africa/.

[53] Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Recommended US Response.”

[54] Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Recommended US Response.”

[55] Eric Schmitt, Declan Walsh, and Elian Peltier, “Coup in Niger Upends U.S. Terrorism Fight and Could Open a Door for Russia,” New York Times, August 16, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/16/us/politics/niger-coup-terrorism-russia.html.

[56] Declan Walsh and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Strikes Qaeda Target in Southern Libya, Expanding Shadow War There,” New York Times, March 25, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/25/world/middleeast/us-bombs-qaeda-libya.html.

[57] U.S. Department of State, Defense Status of Forces Agreement Between the United States of America and Niger, entered into force January 28, 2013, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/13-128-Niger-Defense-NotesCS.pdf.

[58] United Nations, “World Population Projected to Reach 9.8 Billion in 2050, and 11.2 Billion in 2100,” United Nations, accessed February 22, 2025, https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-projected-reach-98-billion-2050-and-112-billion-2100.

[59] PWC, “The World in 2050,” PWC, accessed February 22, 2025, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/research-insights/economy/the-world-in-2050.html.

[60] Michael M. Phillips, “Niger’s Eviction of U.S. Commandos, Drones Derails America’s Counterterror Strategy,” The Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/africa/nigers-eviction-of-u-s-commandos-drones-derails-americas-counterterror-strategy-7e1eff83?msockid=0ca86c631c1e646e080c786a1d0c6506.